Blueprint for The Perfect State

OIJ (#40) Transitioning into the Liberatarian Utopia

Welcome back dear fellow 🧙♂️ Hermits 👋

📢 Today, we’re wrapping up what we started.

Welcome to the inception of the new State.

Buckle up and enjoy the ride, we’re here to redistribute wealth (and knowledge).

Warning: Feelings might be hurt. This is not about low taxes or libertarian caricatures. It’s about redesigning the state to be lean, functional, and accountable.

Quick Recap

Last week, we covered the core theory of inequality, quantified the impact of its flagship policy (the wealth tax), examined the size and influence of government, and posed a few key questions; all centered around whether the current system truly benefits us, based on objective measures like material well-being and progress.

Unlike modern politics, which starts with the status quo and makes minor adjustments, we’re here to throw the baby out with the bathwater. In other words, we’re going back to the building blocks of the state.

This should serve as a blueprint for what a functional state ought to look like.

Getting there from where we stand today requires more than a few steps, and it all starts with a shift in the hearts and minds of individuals. And, as history keeps reminding us, those shifts usually only happen in moments of real crisis.

Argentina is Exhibit XXIV.

We’ll begin by diving into the theory and outlining the major principles, and then quickly shift to the practical side to explore three policies that actually work:

🛠️ Proper (de)Regulation

🧩 Building the Right Incentive Structure

⚖️ Fair Taxation

So… what would a perfect state actually look like?

A Framework for a Functional State

Mr. Thomas Hobbes (you might’ve heard of him) warned us about the creature. It’s called the Leviathan: the all-powerful, all-competent ruler.

Back then (1600s), Hobbes was theorizing about a king with very long arms, one who slowly morphs into a dictator. But what he never theorized is what happens when the ruler becomes abstract, when there is no head.

That’s our current state of affairs: a nameless, faceless shadow embedded in every aspect of our lives for reasons no one can quite explain.

And the funny thing is, we’re the ones who allowed it to creep in.

— Alejandro Yela (22-year-old me)

Yes, I’m quoting myself 😂

Funny enough, I first said these exact words in a dissertation back in 2018, while living in Yokohama, Tokyo 🇯🇵.

They’re as true today as they were eight years ago.

These are ideas that have been simmering for a long time.

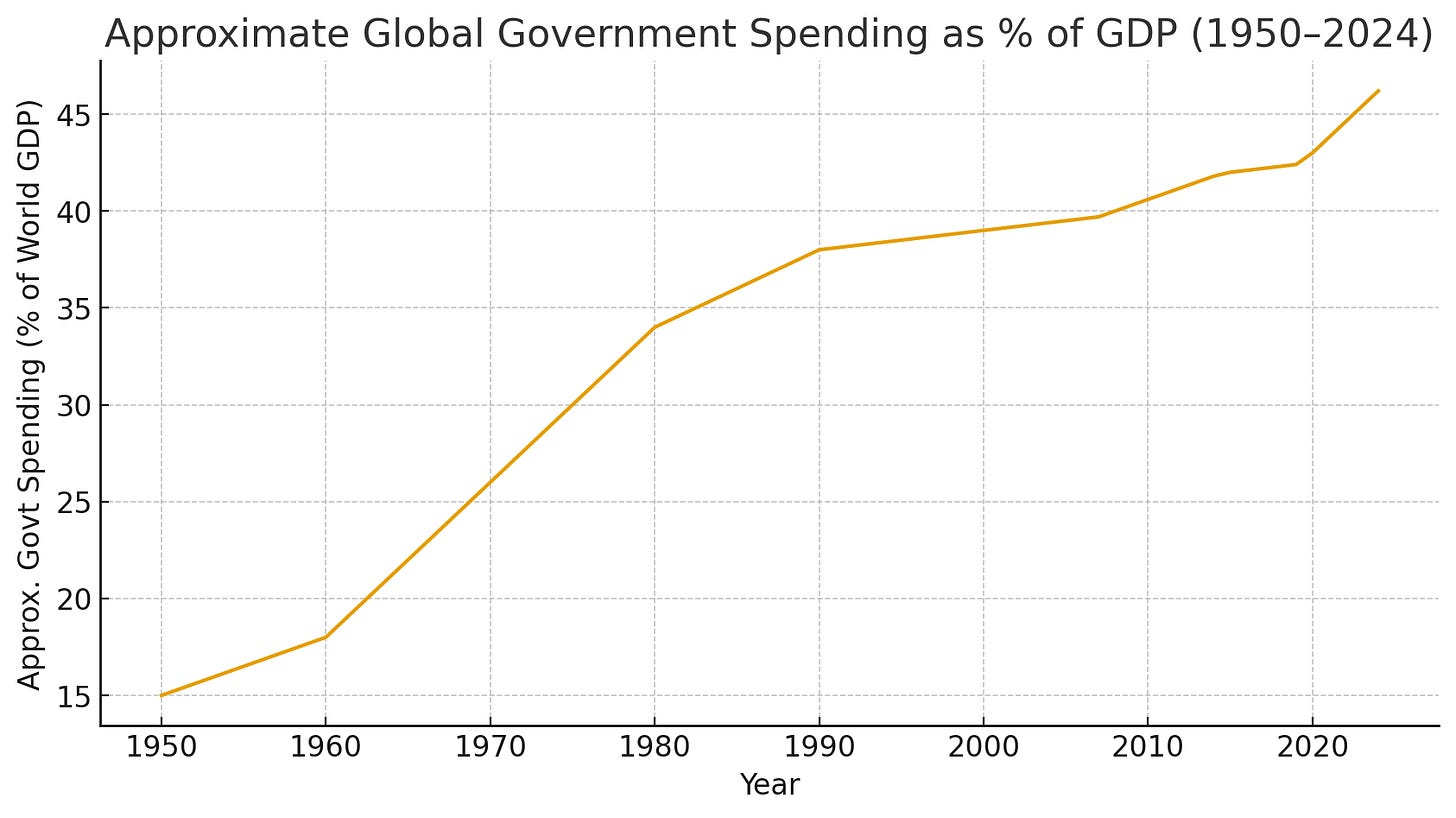

The Ever-Expanding State: 3 Hard Truths Before We Even Think About Reform

The modern state continues to grow in scope and power, often without clear justification or meaningful oversight. As we saw in the previous articles, it has all but taken over every domain, acting as the one force that creates and destroys.

Below is a list of states where government spending accounted for over 50% of GDP, including their peak percentage and the decade in which it happened:

Austria 57.9% (2020s)

Belgium 60.8% (2020s)

Canada 52.5% (1990s)

Denmark 58.5% (2010s)

Finland 56.7% (2020s)

France 62.4% (2020s)

Germany 51.1% (2020s)

Greece 58.2% (2020s)

Ireland 65.1% (2010s)

Israel 69.4% (2000s)

Italy 57.3% (2020s)

Netherlands 55.2% (2010s)

Norway 58.2% (2010s)

Portugal 51.4% (2010s)

Spain 52.3% (2020s)

Sweden 55.1% (2000s)

United Kingdom 50.6% (2020s)

Of course, some of the spikes occurred during crises, such as 2014’s European debt scare and 2020’s COVID-19 shock, but the larger trend remains unchanged.

Government spending has been steadily drifting upward for decades.

In fact, it has more than tripled on a global scale since the end of World War II.

This brings about several consequences, but the primary one is wealth redistribution. And contrary to the usual narrative, redistribution doesn’t flow from the rich to the poor.

The data makes this clear: the ever-growing pressure falls on the least organized groups in society… the middle class, young people, entrepreneurs, and anyone who doesn’t have a lobbyist on speed dial.

And the spoils flow to the organized groups, typically those that make up a strong voting majority, such as retirees, public officials, labor unions, and, of course, the State itself.

And in all this, we forget that the State manufactures bureaucracy, regulation, and endless paperwork, but not the goods and services that actually improve our lives.

Even worse, whenever the State tries to venture into productive asset creation, it usually does so uneconomically. It doesn’t create a good, it creates a… what’s the opposite of a good? A bad?

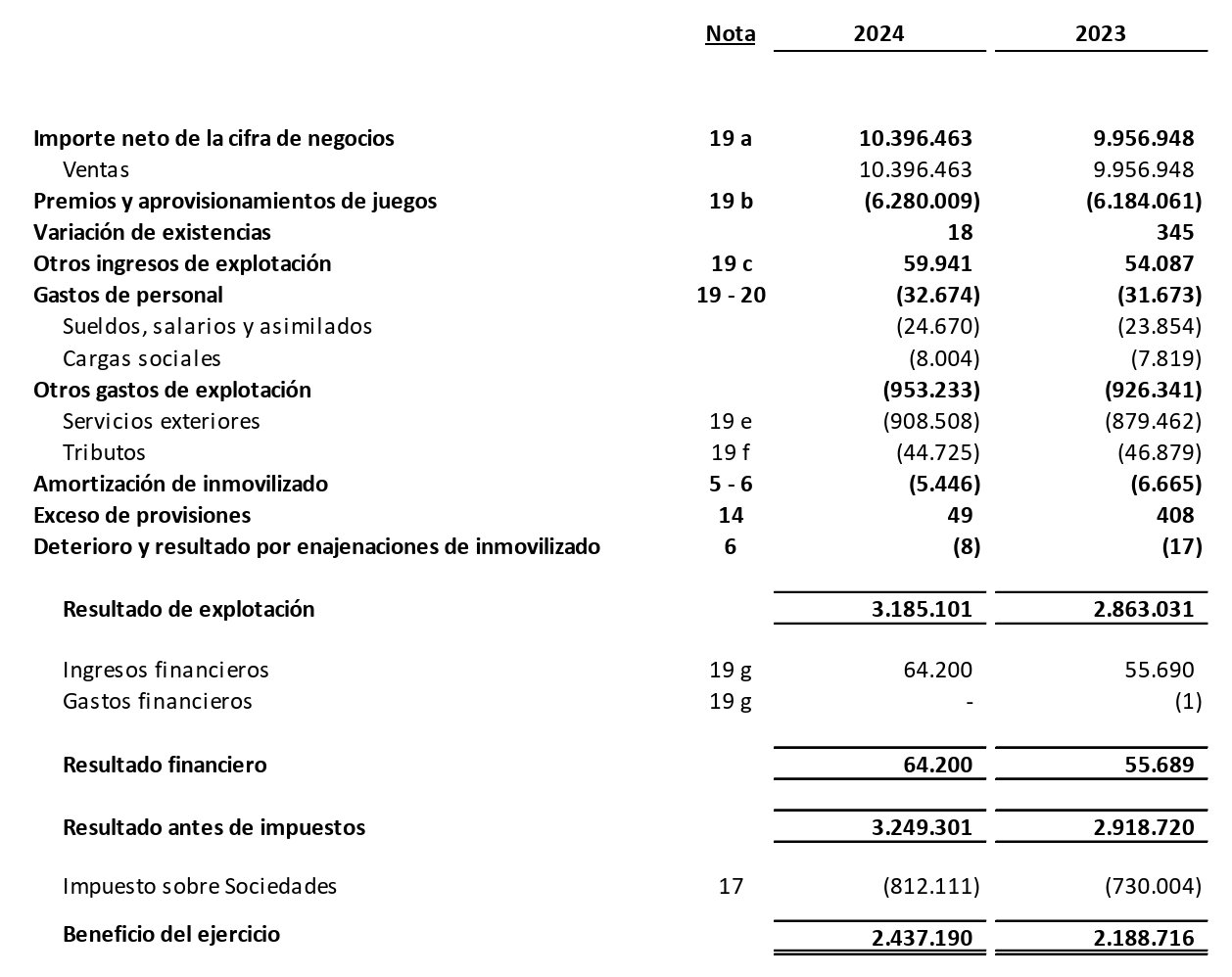

This is why the only non-deficitary government-owned entity in Spain is Loterías y Apuestas del Estado, which, by the way, reported a very healthy €2.4 billion in net income in 2024.

Great job, team… the lottery 😂😂👏

The State consumes value; it doesn’t create it.

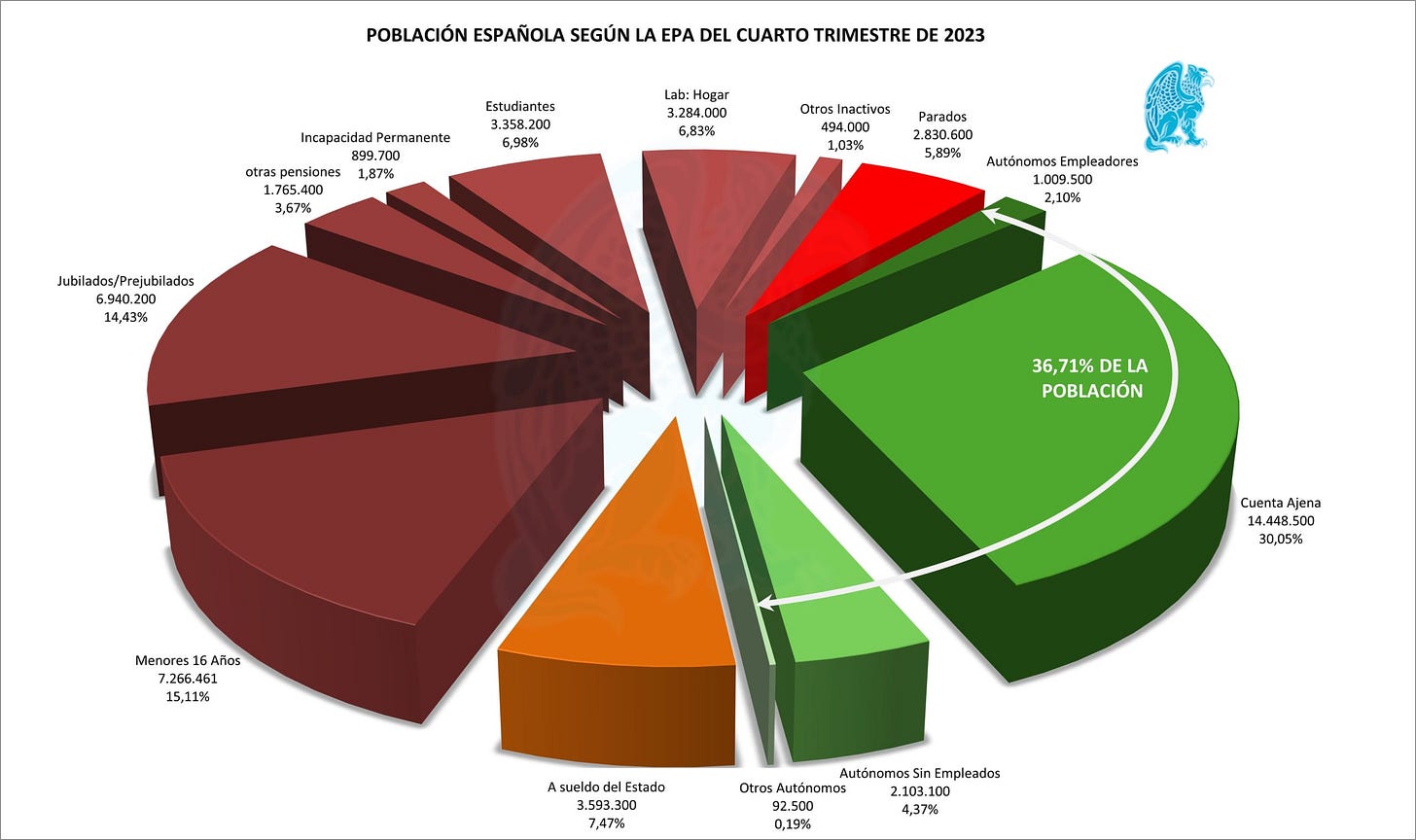

Which means, at best, roughly 40%-ish of the population (including retirees, minors, etc., in the denominator) is effectively producing everything.

We’re not exaggerating.

This graph blows my mind. In Spain, just 36.7% of the population is responsible for producing 100% of the country’s goods and services.

The creation of wealth, prosperity, justice, education, stability, opportunity, dignity, you name it… is being carried out by a shrinking minority of the population.

This creates all kinds of externalities and, worse, a pervasive feeling of being stuck in place. The productive side of society often feels strangled by a majority that somehow never seems to have enough.

Hard turth #1: The state consumes.

While individual actors within government may genuinely care, the state itself is fundamentally impersonal… and it becomes even more so the further removed it is from the people it governs.

Your local mayor is far better at understanding and responding to real needs than a national president, and certainly more so than bureaucrats sitting in the capital of a “super-state” like the European Union.

Incentives are distorted from the start, and this is especially true when spending other people’s money.

The state is effectively playing Monopoly with someone else’s hard-earned cash. The risk feels abstract, and the accountability even more so.

This dynamic becomes even more extreme when the state can create its own currency (through central bank printing or government debt) and enforce its use, further distancing decisions from real-world consequences.

The result is fairly predictable. We’ll get bloated bureaucracy, layers of inefficiency, and a growing disconnect between what citizens actually need and what the system produces.

Hard turth #2: The state does not care about the individual.

There are two prevailing themes occurring worldwide related to the State. The first is massive marketing campaigns, and the second is merit (re)attribution.

For starters, we have a permanent series of marketing stunts endlessly cycling through our daily lives. There are several objective measures that we can verify.

The most explicit proxy is ad spending data:

In 2023, the Spanish Government consolidated itself for the second consecutive year as the largest advertiser in Spain, spending €90.4m on institutional advertising.

This figure, published by the Annual Advertising Execution Report (official source) from the Ministry of the Presidency, exceeds by more than 30% the €72m invested by L’Oréal, followed by the €68m spent by Stellantis and €64m by Procter & Gamble.

Note that the original government budget for 2023 ad spend was €145m.

And 2023 was actually a down year… The pattern becomes obvious when you look at the numbers: €102m spent by the government in 2022 and €138m in 2024.

And it’s not just Spain, this happens across most developed countries. Which raises a pretty obvious question: why on earth are we spending our hard-earned money on marketing campaigns for the State? What exactly is it trying to sell?

More subjectively, we can feel the State’s presence everywhere. Just think about the news cycle. How much of it is nothing more than the daily theatre of politics.

And this becomes painfully obvious whenever politicians go on holiday. Ever notice how suddenly there’s… no news? Strange, isn’t it?

The second point concerns merit attribution. Whenever something good happens, the State rushes to position itself as a key contributor. And when things go wrong (lack of preparation, failing infrastructure, poor planning), it suddenly distances itself as if it had nothing to do with it.

It only wants credit for the good stuff.

This is especially obvious with historical achievements. Take education in Spain: for boomers and earlier generations, the bulk of teaching was done not by the State but by the decidedly imperfect yet undeniably active Catholic Church.

Spain’s mass literacy is largely thanks to them, yet modern politics insists on pretending the State “created” both education and the educated from scratch.

And it gets worse. Sometimes this theatre produces truly absurd narratives.

The one that always comes to mind is Argentina’s former Minister of Labor choosing “winning the World Cup” over fixing inflation… as if the government had anything to do with winning the cup.

Hard turth #3: The end goal os the state is self preservation.

The Need for a Strong Constitution

We’ll start with the basics, but don’t mistake basic for undeveloped. Having a few clear, well-defined pillars is exactly what makes the whole thing work.

Originally designed to protect citizens from the state, the constitution must now be refocused into a functional document that clearly (and explicitly) defines and limits state powers.

This is akin to doubling down on what far smarter people than us already did (like the US founding fathers). However, instead of emphasizing the rights of individuals beyond life, liberty, and property, this document should focus on explicitly limiting the obligations and functions of the State.

Just as penal codes define crimes before punishment can occur, the constitution should pre-define the State’s competencies.

Any and all ambiguity should be removed.

Core Principles

1. Natural Rights

At the core of any functional state are Natural Rights (life, liberty, and property), rooted in classical natural law from Greek philosophy. These aren’t privileges granted by the State but inherent conditions of human existence. Everything else is downstream, and, more importantly, does not require explicit and universal protection.

We have to remember that rights and obligations are two sides of the same coin. Whenever you’re granted a right, someone else carries the corresponding obligation.

It would be inconsistent to demand a limited state without first accepting that our rights must be limited in number, but extremely powerful in nature.

2. Preservation of Freedom

The second pillar is the Preservation of Freedom, which means building safeguards against the constant temptation of populist, short-term fixes and the political impulse to find scapegoats instead of solving real problems.

A free society begins to collapse the moment emotional politics overrides rational structure. In a democratic system, this implies that any change to the basic law must require near-consensus (at least 80% approval) and should be decided directly through a referendum, rather than indirectly through representatives.

3. Fair and Simple Taxation

To support this framework, Taxation must be Fair and Simple. Ideally, the system relies on a single, clearly defined tax such as a land tax.

This is easily achieved when the tax is based on immovable assets that are hard to manipulate, making calculation straightforward and reducing the need for bureaucratic collection.

By avoiding taxes on labor and capital, the system encourages productivity, upward mobility, and entrepreneurship.

Optional or luxury consumption taxes can exist as straightforward “pay if you use” mechanisms, but anything that penalizes creation, work, or investment should be off the table.

We also want to prevent the current system of double or (even) triple taxation.

In Spain, property taxation spans three stages: purchase, ownership, and sale.

When buying, new-builds are subject to 10% VAT plus 1–1.5% stamp duty (AJD), while resale properties pay 6–10% transfer tax (ITP) depending on the region.

Once owned, properties incur the annual IBI municipal tax of roughly 0.4–1.3% of book value, and owners may also face wealth tax (region-dependent) and, for non-residents, imputed rental income tax.

When selling, gains are taxed at 19–24% for residents, 19% for EU/EEA non-residents, and 24% for others, plus the municipal “Plusvalía” land-value tax based on book value appreciation.

And this is all before considering that the money used to buy the property has already passed through multiple layers of VAT and income taxes.

Almost all of these taxes should be eliminated.

The only one that makes sense to keep is a simple municipal tax of around 2-3% of the property’s book value.

This would have two clear benefits: it would encourage fluid transactions by minimizing distortions in supply and demand, and it would protect access to a basic necessity, namely owning a home.

Having a house would remain very affordable, while accumulating ten properties becomes far less attractive for an individual or company.

Here, I’m proposing a property-based tax, but an income tax, such as a flat tax or a negative tax (deductibles), could be just as defensible. The core idea is simply to have a clear, effective, and minimally distortive way of gathering resources for communal use.

Core Competencies

Where do we actually need a State?

We’ve discussed limiting its competencies, but what are the specific areas where the State can operate effectively?

The answer is simple: once the State’s powers are strictly limited, we grant it the monopoly on violence.

This makes for an impartial third party limited to three essential roles:

Internal Security. Enforcement of the legal order

External Security. Protection of borders and national sovereignty

Legal Order. Arbitration and enforcement of civil, penal, and commercial law

These principles lead to what authors and academics call a minarchist state.

Short of the anarcho-capitalist ideal, this is the closest we can get to a functional, organized, minimalist State.

By granting the State the power to preserve the rule of law, we establish a nearly neutral party that intervenes only when necessary… essentially government on demand.

In day-to-day life, we don’t need it hovering over us, but when a dispute arises between citizens (or outsiders), there is an authority capable of resolving it and enforcing the outcome.

External security… to put it simply, a nation needs to command enough respect so that its neighbors don’t randomly decide to stroll in and take its land.

Legal Simplicity and Reform

As for laws and regulations, these would emerge from two sources: first, municipalities could enact rules for day-to-day local matters; and second, jurisprudence, or the accumulation of decisions from past disputes.

The only real exception would be a basic penal code, since that’s the one area where you genuinely need technocrats (subject-matter experts) to establish a foundational code of conduct. You can’t charge someone with a crime that hasn’t been previously defined.

So yes… a one-time effort to create the penal code, and everything else handled through what is essentially the modern equivalent of arbitration.

By voluntarily granting the monopoly of violence to a third party, we ensure that an impartial arbiter handles societal conflicts. We don’t want people taking up arms over trivial issues like a family feud.

We could also introduce a cap on the number of active laws: any new legislation would require removing or replacing an existing one. This cap would apply to local codes; jurisprudence wouldn’t need such limits, since case law naturally refines itself by resolving specific situations with analogous circumstances.

Local Governance and Autonomy

Because we’ve identified a conflict between the needs of the represented and the execution of the State, power should reside at a very local level.

Local governments should have independent revenue and spending authority, meaning they collect their own taxes and are fully accountable for how those resources are deployed. And since taxes are limited and the functions of government clearly defined, both the scope and frequency of their interventions remain naturally constrained.

However, unlike a “central” government, municipalities can directly assist with more intricate issues like education, infrastructure, healthcare, and pensions. Of course, only in their simplest, most functional form.

Local communities are far better than distant bureaucracies at designing systems that match their demographics, values, and economic realities.

For instance, local employers, employees, and the municipal government could collaboratively determine how wages are allocated to create “localized rights.” An ideal setup might be something like an 80/10/10 structure: 80% paid directly to the employee, 10% dedicated to health insurance, and 10% allocated to a pension plan.

Alternatively, workers could directly unionize if they choose, and redirect that 20% toward the union instead, in exchange for healthcare, pension plans, and broader representation.

Whatever the mix, it is voluntary and directly benefits productive members of society.

In isolated communities, this may sound utopian, but when municipalities are forced to compete for both employees and employers, they naturally develop incentive schemes that benefit everyone involved.

Again, for example, if taxes are based on land value, local governments are incentivized to maximize that value by creating attractive, productive spaces for their citizens.

This could lead to two outcomes: densely populated, highly productive hubs like Hong Kong, or spacious, high-end areas that attract wealthy residents like New York. Either way, governments would be driven to enhance the value and quality of their communities rather than extract from them, as it is in their own self-interest.

Local governance also helps minimize corruption and keeps spending closely aligned with community needs.

Lobbying becomes basically irrelevant.

Los empresarios no pueden comprar favores que los políticos no tienen para vender

— Javier Milei

Businessmen can’t buy favors that politicians don’t have the power to sell

— Javier Milei

And when you combine limited government revenue with the removal of things like public works spending, permitting, and other discretionary levers, you arrive at what academics and practitioners call a night-watchman State.

Local authorities should be empowered to the point where they could threaten secession. That possibility acts as a powerful check on any attempt by central authorities to accumulate excessive power or impose one-size-fits-all mandates.

We want to push the relationship between center and periphery towards forced cooperation rather than coercion.

Democracy and Leadership

In this system, democracy is very much alive, especially at the local level.

Direct voting is the preferred method. Essentially, what we commonly refer to as referendums.

Local citizens decide everything, and I mean everything: taxation, service levels, migration policy, even the possibility of secession.

For example, recently, the canton of Zürich, Switzerland, voted on local taxes:

On 18 May 2025, voters in the Canton of Zürich rejected a proposal that would have reduced the corporate profit tax rate from 7% to 6%. By saying no to the cut, the electorate effectively chose higher tax revenues than they would otherwise have had.

The cantonal government and business groups argued for the reduction to keep Zürich attractive versus other cantons and to secure jobs, but a coalition of left-wing parties, unions and NGOs campaigned against it, warning that it would mainly benefit larger companies, squeeze public finances, and shift the burden onto households and municipalities.

A majority of voters sided with the latter view, preferring to preserve funding for services like education, social spending and infrastructure rather than join a perceived “race to the bottom” on corporate tax.

Local politicians would mostly be volunteers (also the case in Switzerland), since limited government revenues don’t justify (or require) large salaries. This naturally encourages more vocational, service-driven public servants.

More importantly, it removes most of the incentives for psychopaths and power-seekers to take over, because real authority rests with direct (individual) democracy rather than with representatives holding concentrated power.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Wherever possible, local government should outsource service provision through competitive markets. This is typically done via Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), which align public needs with private-sector efficiency.

I used to be heavily involved in these and know the mechanics quite well.

First, don’t confuse PPPs with subsidies. There’s no need for a discretionary payout to the private sector. What they do involve is a concession, structured around how different risks are allocated between the parties. Properly designed, a PPP is about risk-sharing and performance, not handouts.

At the risk of oversimplifying, we’ll briefly outline the key element of a PPP.

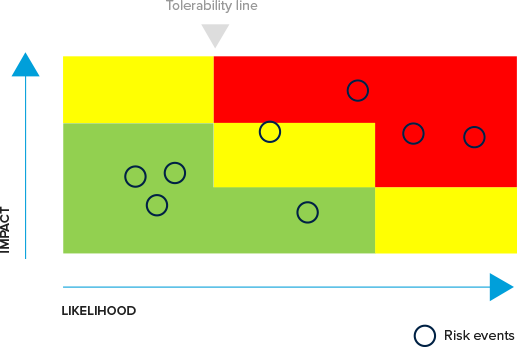

That element would be the risk matrix. This is where local authorities and private operators, designers, and builders negotiate who takes responsibility if a certain event occurs.

For example, time extensions. What happens if there are delays, cost overruns, design flaws, or the asset simply isn’t completed on time? In most cases, the builder absorbs those costs and takes on the loss.

Another example could be demand risk. What happens if actual usage or revenue (traffic, users, occupancy, etc.) is lower than expected? In those situations, local authorities typically set a minimum charge or availability payment and assume that portion of the risk.

This would come together, for instance, if a community needs cheaper energy.

A modular nuclear plant is a good illustration: the private company finances and constructs the facility, assuming all construction and operational risks, while the local government guarantees a minimum price per unit of energy regardless of demand (paid by users).

This arrangement requires no discretionary public spending, yet it demonstrates how local authorities can use collective bargaining power to secure better outcomes for their residents.

This framework can be applied to any and all coordinated services… infrastructure construction, education, health insurance, pension plans, landscaping, you name it.

Nice to Have (NTH)

Up to this point, we’ve covered the elements that are necessary for the State to function.

The following aren’t strictly required, but they’re certainly nice to have, as they can boost growth/progress in powerful, unexpected ways.

Personally, I see them as pure upside. Each one relies on constant trial, error, and optimization, which naturally pushes society forward.

There are plenty of cases to illustrate this, but we’ll use immigration and technology as our examples.

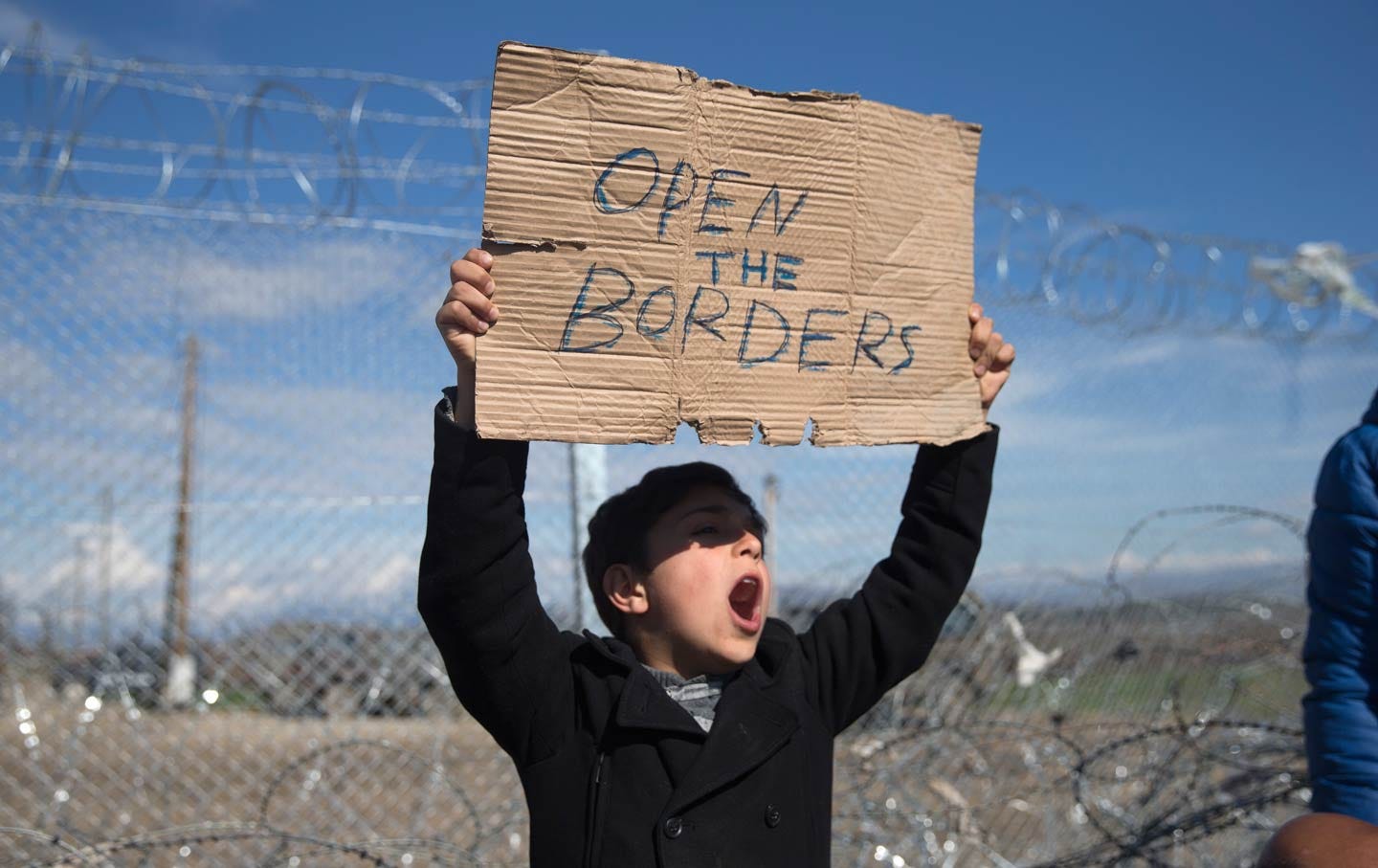

Immigration. Open but Neutral

Immigration should be unrestricted in principle, but newcomers should receive no special benefits and no disproportionate influence over the system.

Equal opportunity must exist in property ownership, trade, and labor. There are no initial entitlements, no permits, no bureaucracy, just a genuinely level playing field.

This doesn’t mean locals aren’t rewarded for their time and effort. The longer you live in a prosperous region, the more you benefit from the compounding effects of localized growth.

For example, homeowners in prosperous areas will naturally see their property values rise. Workers who have contributed to mandatory savings for ten years under competent local rules will see greater returns and security.

And the reverse is also true. If citizens are dissatisfied with how a region is managed, they are free to leave. Nothing ties them down.

For example, a strong region with mandatory savings policy might collectively negotiate access to three recommended ETF options (PPP). Over a 5–10 year period, a competent recommendation will compound nicely, while an incompetent one will simply fail to deliver, making performance immediately visible. Since your savings account is yours and yours alone, you will reap the benefits and pay for the losses.

Incompetence is punished by out-migration; competence is rewarded by attracting people and capital. The greater the competition between regions, the more powerful this dynamic becomes.

Embrace Technological Alternatives

Decentralized technologies, such as blockchain, should be free to compete directly with traditional state functions. Their purpose isn’t to replace the State, but to challenge it, pressure it, and keep it honest.

Take property registration as an example. There is no compelling reason why recording ownership on Ethereum (or any other robust blockchain) should be considered less valid than doing so through a traditional notary’s office.

A secure, publicly auditable ledger can provide equal or even greater transparency, permanence, and resistance to tampering. If an alternative system is cheaper, faster, and more reliable, the State should not stand in its way.

The State must not pick technological winners.

It shouldn’t force society into one method purely because it’s the conventional one, nor should it block emerging solutions that may outperform legacy institutions. Allow competing systems to operate side by side, and let the best ones prevail through actual performance instead of regulation.

Take Aways

1. Build a system that maximizes prosperity and freedom

The goal of this political architecture is to create the conditions under which people can thrive.

That means protecting private property, minimizing coercion, and ensuring that individuals can maximize value creation.

Once again, private property takes center stage. And yes, we often forget this, but our wages (our income) are the very first form of private property.

Prosperity and freedom aren’t accidents; they emerge when incentives reward initiative, risk-taking, and responsibility.

2. Foster robust institutions that resist short-term populism and central planning

Great civilizations collapse when institutions bend to emotional waves, election cycles, or “temporary” emergency powers.

Durable institutions must be structured to absorb pressure, not capitulate to it.

They should be transparent, predictable, and deliberately insulated from political whims so that long-term thinking always outweighs crowd-pleasing theatrics.

Populism fades; strong institutions endure.

3. Let innovation and decentralized systems flourish within a clear, limited constitutional framework

When rules are simple, known, and strictly limited, everything outside those boundaries becomes a playground for innovation.

Decentralized solutions, whether technological, social, or economic, compete organically to deliver better results… Blockchain systems, private arbitration, AI-driven services, even local governance models.

All should be free to challenge traditional state functions.

Competition, competition, competition.

Note: After editing this text for the twentieth time, reading it out loud genuinely makes me emotional. Seeing how far we’ve come on one hand, and how much potential still lies ahead on the other, honestly brings a tear to my eye.

It makes me profoundly optimistic about the future. If we’ve managed to achieve all of this with both legs essentially tied together (voluntarily!), just imagine what we could do once incentives are finally aligned.

🙏 Feel free to ❤️ and comment so that more people can discover and enjoy this Substack 😇

¿Quién vigila a los vigilantes?

Where I agree: the "overhead" on the State is bloated, and the shareholders (us regular folks) aren't seeing a return on our investment. I appreciate the focus on a Land Value Tax; asking the people who own the "stadium" to pay for its maintenance, rather than taxing the players for working hard, is a financially sensible strategy.

However, a warning regarding those Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) comes from my time inside the beast. You mentioned "risk-sharing," but back in my day on Wall Street, we called it privatization of gains and socialization of losses.

Handing essential infrastructure over to a private entity with a monopoly often results in a new landlord who knows you have nowhere else to go, rather than delivering "free market efficiency." Be very careful that your "risk matrix" doesn't end up with the taxpayer covering the downside while a private equity firm extracts the dividends. We should aim to fire the bad managers, not sell the factory for parts.

Sharp writing, though. It’s a conversation we need to have.