🧗 The Lost Decade: Examining Japan's Economic Downturn of 1989-1991

OIJ (#10) Short essay exploring the bubble economy and its aftermath. Elements that led to the - so called - Lost Decade

My dear fellow Hermits 👋

Welcome back to 🧙♂️ The Hermit 🧙♂️

ICYMI:

💼 The Hermit Portfolio: July Update

📝 Company Updates: Century Casinos Q2 2024 Update

🎧 The Hermit Podcast: Limes Schloss Clinics Interview w/ CEO

If you haven’t yet, subscribe to get access to this post, and every new post

Preliminary note

Here’s a post that adopts a completely different approach. This one leans more towards the academic side, drawing heavily from my readings and experiences back in 2018 while living and working abroad in Tokyo, Japan.

Please let me know if you enjoy this type of content by leaving a ❤️ and a comment.

Executive Summary

This essay explores the causes and effects of the Japanese crisis of 1989-91. The crisis stemmed primarily from poorly executed financial liberalization, asset price deflation, non-performing loans, risky investments, the Plaza Accords, failures in the tax mechanism, and the land lease law. These factors contributed to a bubble economy that burst, plunging Japan into the ‘Lost Decade’, characterized by long-term deflation and widespread economic impact. The crisis adversely affected the banking sector, land prices, and investment, as evidenced by severe declines in the Nikkei Index. Although the government implemented various measures before, during, and after the crisis, these efforts fell short of achieving their objectives. This essay also proposes alternative measures and discusses the ongoing consequences of the crisis that persist to this day.

Introduction

The Japanese crisis of 1989-1990 exemplified how unchecked optimism and abundant capital can drive a nation to make disastrous decisions. The end of the 1980s ushered in a new era of economic distress that would culminate in the 2008 global financial crisis nearly 20 years later. During this period, financial deregulation allowed institutions to profit from indiscriminate lending. Politicians enjoyed high approval ratings due to ever-rising asset prices, and the Yen gained global prominence for both positive and negative reasons. Japan transitioned from an economy fueled by domestic savings to one reliant on foreign investment and debt.

Amid progress, excess became the norm, leading to unsustainable debt accumulation and widespread loan defaults. Financial institutions' speculative investments in land backfired as property values plummeted, causing the money market to contract to a mere 3% of its previous size.

In examining 'The Lost Decade,' we identified several critical issues, including the government's response, the resilience of the Japanese people, and the international community's reaction.

In each case, we pinpointed the root problems and proposed alternative solutions. Instead of postponing the inevitable, addressing the core issues directly could have allowed Japan to flourish in the long term. However, the short tenure of politicians often led to a focus on immediate, personal gains rather than long-term national benefits.

The issues of debt and overvaluation/over-investment were not solely domestic; external influences played a significant role. Our research into interactions with G7 countries, particularly the United States, revealed the impact of Federal Reserve actions and White House policies on Japan's economic situation, especially concerning account balances and Yen appreciation.

Lastly, we explored the lessons the world can learn from this crisis. Prevention, more often than not, is the best strategy for avoiding a repeat of the Japanese crisis of 1989-1990.

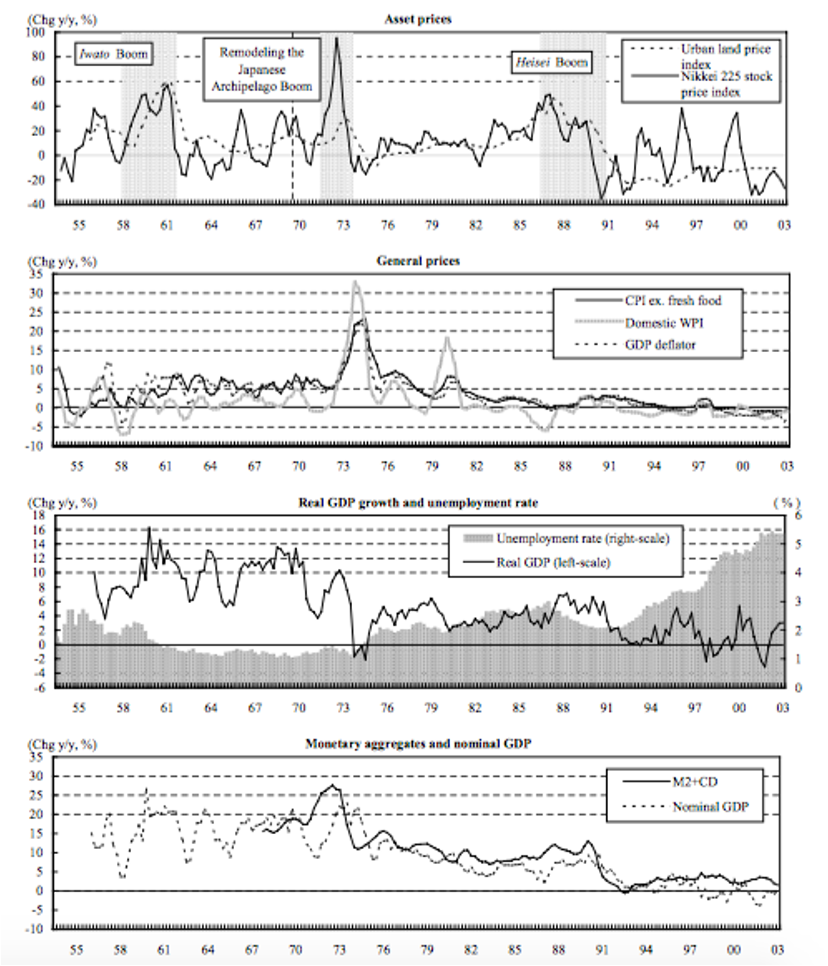

Main economic indicators

The history leading up to the actual crisis is fascinating because some events, if properly analyzed, could have served as warnings for what was to come. Similar to other crises, Japan experienced a bubble, primarily caused by an overheated economy and excessive savings (in the form of illiquid assets) by consumers and companies, which ultimately slowed the economy down. This economic bubble resulted in high unemployment, capital flight, and a sharp decline in the stock markets. Below are the key events that led to Japan's financial crisis, commonly known as the Lost Decade.

The first event worth highlighting is the Plaza Accord, signed in New York in 1985. This agreement aimed to promote economic growth by devaluing the U.S. dollar, which was necessary due to the United States' current account deficit. On the other side, European nations and Japan had current account surpluses and negative GDP growth, which hurt their external trade. The Plaza Accord can be seen as the starting point of the crisis, setting the stage for economic disaster for Japan.

With Japan's signature, the Yen appreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar, severely impacting Japan's trade advantage. Some argue that this was a strategic move by the United States to curb Japan's growing economic power. However, for political reasons, Japan was willing to allow the Yen to appreciate in exchange for the U.S. not imposing punitive tariffs on Japanese exports.

Later, in 1986, significant changes in monetary policy occurred. The government repeatedly reduced the official discount rate throughout the year. The first reduction happened on January 30, when the rate was cut from 5.0% to 4.5%. Subsequently, on February 22, 1987, the official discount rate was further reduced to 2.5% following the Louvre Accord. This agreement led the Bank of Japan to seek monetary policy tightening and maintain a steady discount rate.

In light of these circumstances, the Tokyo Economic Summit Conference took place to establish a framework to stabilize the economic environment. Additionally, the Mayekawa report aimed to “attain the goal of steadily reducing the nation’s current account imbalance to one consistent with international harmony” by “setting [it] as a medium-term national policy goal.” The report included recommendations for “basic transformations in the nation’s trade and industrial structure” and “striving for economic growth led by domestic demand.”

Political discussions led to further reductions in the discount rate as mentioned above. Japan struggled to find a stable rate for its economy, considering the impact on its external economy and how the discount rate would affect it. By continually lowering the rate, Japan aimed to ensure that the United States would continue to cooperate on exchange rate issues.

Another significant event is Black Monday of 1987, recognized as the worst stock market crash in history. On that day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted by 508 points (Black Monday: Remembering the Worst Day in Wall Street History, 1987). This crash also affected Japan's economy, exacerbated by the volatility of its discount rate. Consequently, the Nikkei Index experienced a substantial impact, as detailed below.

On January 12, a 666-point plunge in Tokyo's key Nikkei average kicked off a 71-point sell-off in the Dow-Jones industrials. A few weeks later, a 600-point plunge in Japan sent the Dow tumbling 60 points in the first half-hour of trading. They used to say that when the U.S. sneezes, the rest of the world catches pneumonia. No more. Japan's awesome financial and economic muscle has reached the point where its kushami, or "sneezes," can make Wall Street sick. - “When Japan Gets the Jitters, the Rest of the World Trembles," Business Week, Feb 12, 1990

However, opinions were divided on how Japan's economy could impact the global market.

Many of the people who thought Japan's stock market was stupendously overpriced worried that the bubble's inevitable burst would set off a chain reaction of stock market plunges around the globe. So far, there is no sign of that doomsday link. While the Tokyo stock market is down 14.37% —this year,—grn^V marlcp.r- elsewhere in the world haven't fallen as steeply and don't seem to be following the Nippon lead. - “So Far, Tokyo Isn't Dragging Rest of World Markets Down," Wall Street Journal, Feb 27, 1990.

As shown above, two highly contradictory articles discussed the instability of the Japanese economy. This contrast highlights the lack of stability and the extreme levels of volatility it exhibited at the time.

Following these events, Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru decided to pass a bill introducing a consumption tax to promote austerity in the country. In April 1989, a 3% consumption tax was imposed, but shortly afterward, the Prime Minister was forced to resign due to a corruption scandal. Subsequently, monetary tightening began, and the discount rate started to increase. On May 30, 1989, the rate was raised from 2.5% to 3.25%, and by August 30, 1990, it had surged to 6.0%, partly influenced by the Gulf Crisis.

The Japanese Prime Minister Kaifu's response was also flawed; his heavily political approach damaged the economy, especially the 600 billion yen lent to Iraq by Japanese corporations. Japan's difficulty in separating economics from politics exacerbated the crisis. As a result, stock prices plummeted to half their peak level, solidifying the crisis in the country.

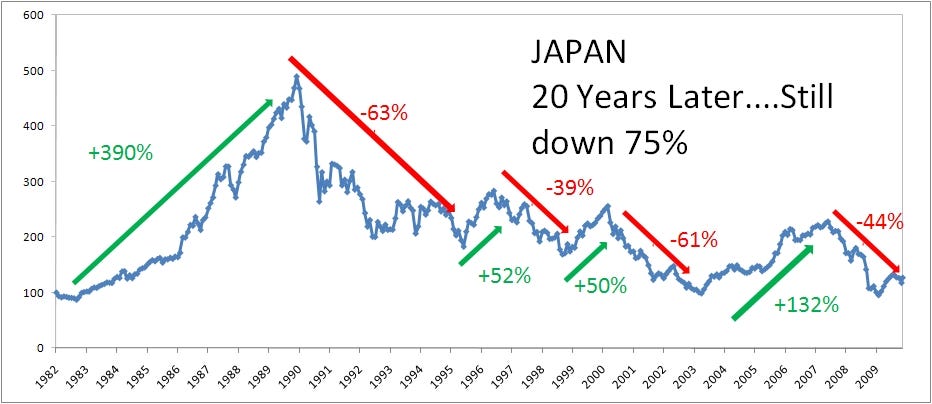

The Japanese yen continued to appreciate against the US dollar, the Nikkei 225 dropped to 22,984, and land prices in Tokyo fell dramatically. To this day, Japan hasn't fully recovered, despite the Nikkei reaching new highs in 2024.

Possible Factors behind the Japanese Asset Price Bubble Burst

A. Poorly Executed Financial liberalization

When the United States was in recession in the early 1980s, the U.S. government attributed part of the problem to the exchange rate imbalance between the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen, although the fundamental issue was the declining competitiveness of domestic producers. To achieve a depreciation of the U.S. dollar and an appreciation of the Japanese yen, the United States focused on removing financial restrictions in Japan and increasing the demand for the yen.

At the time, Japan's financial restrictions prevented the yen from being freely purchased and invested in by foreign countries. In 1983, the United States and Japan established the Committee for Yen and the U.S. Dollar to reduce exchange rate friction. Through this committee, the United States strongly urged Japan to deregulate and ease restrictions on financial and capital transactions.

As a result, in 1984, Japan removed restrictions on future exchange transactions, allowing not only banks but also companies to engage in currency trading. Later that same year, regulations on converting foreign funds into Japanese yen were also eliminated. The abolition of these financial restrictions opened up the Japanese financial market to international investors, significantly increasing the demand for the Japanese yen.

Moreover, this shift changed how Japanese businesses obtained funding. They began using the capital market instead of relying on the banking system, despite traditionally being considered deposit savers. This shift led to changes in bank behavior, as major firms were no longer keen to use banks as their primary source of funding. Consequently, banks were forced to aggressively promote loans to smaller firms backed by properties. Around 1987-1988, banks also began lending to individuals backed by their properties.

This change had a significant impact on the Japanese asset bubble. Firstly, cheap and easily available loans reduced funding costs for speculative purposes. Secondly, rising stock prices lowered capital costs, facilitating capital market financing. Lastly, the simultaneous increase in land and stock prices boosted the value of assets held by corporations. This effectively increased their funding sources by raising the collateral value of their assets.

At the same time, this financial deregulation enabled firms to borrow substantial amounts of money to invest in commercial real estate, private land, and - funnly enough - golf club memberships. Financial deregulation provided corporations with various financing options, reducing their dependency on banks for funding. During the 1980s, Japanese banks shifted their primary focus of credit supply from the manufacturing sector to non-traded goods industries, such as real estate, finance, and other services that were not subject to strict global competition.

B. Asset Price Deflation

Financial liberalization and inadequate laws led to a significant increase in asset price levels. In the first half of the 1980s, controls on capital movements were dismantled, deposit interest rates were deregulated, and new financial institutions were established. As banks lost large firms to international capital markets and domestic securities markets, they sought alternative lending opportunities in small and medium-sized firms. These firms could borrow for risky or low-return projects based solely on real estate collateral.

Additionally, the monetary policy implemented in the second half of the 1980s further fueled asset price inflation. The Bank of Japan’s official discount rate was halved to 2.5% between the end of 1985 and early 1987 and remained unchanged for two years, despite robust economic growth.

By 1989, even the Ministry of Finance recognized that the bubbles in real estate and stock prices were unsustainable, anticipating that price levels would eventually decline. Contrary to their belief, total bank assets plummeted from 508 trillion yen in 1989 to 491 trillion yen in 1990. Monetary policy was sharply tightened starting in May 1989, with the official discount rate being raised incrementally to 6 percent by August 1990.

Equity prices began to fall in early 1990, and the Nikkei index declined by over 60 percent from its peak at the end of 1989. In response, the Ministry of Finance introduced guidelines limiting total bank lending to the real estate sector. The fall in stock prices, which began in early 1990, continued until the end of 1992.

C. Non-Performing Loans

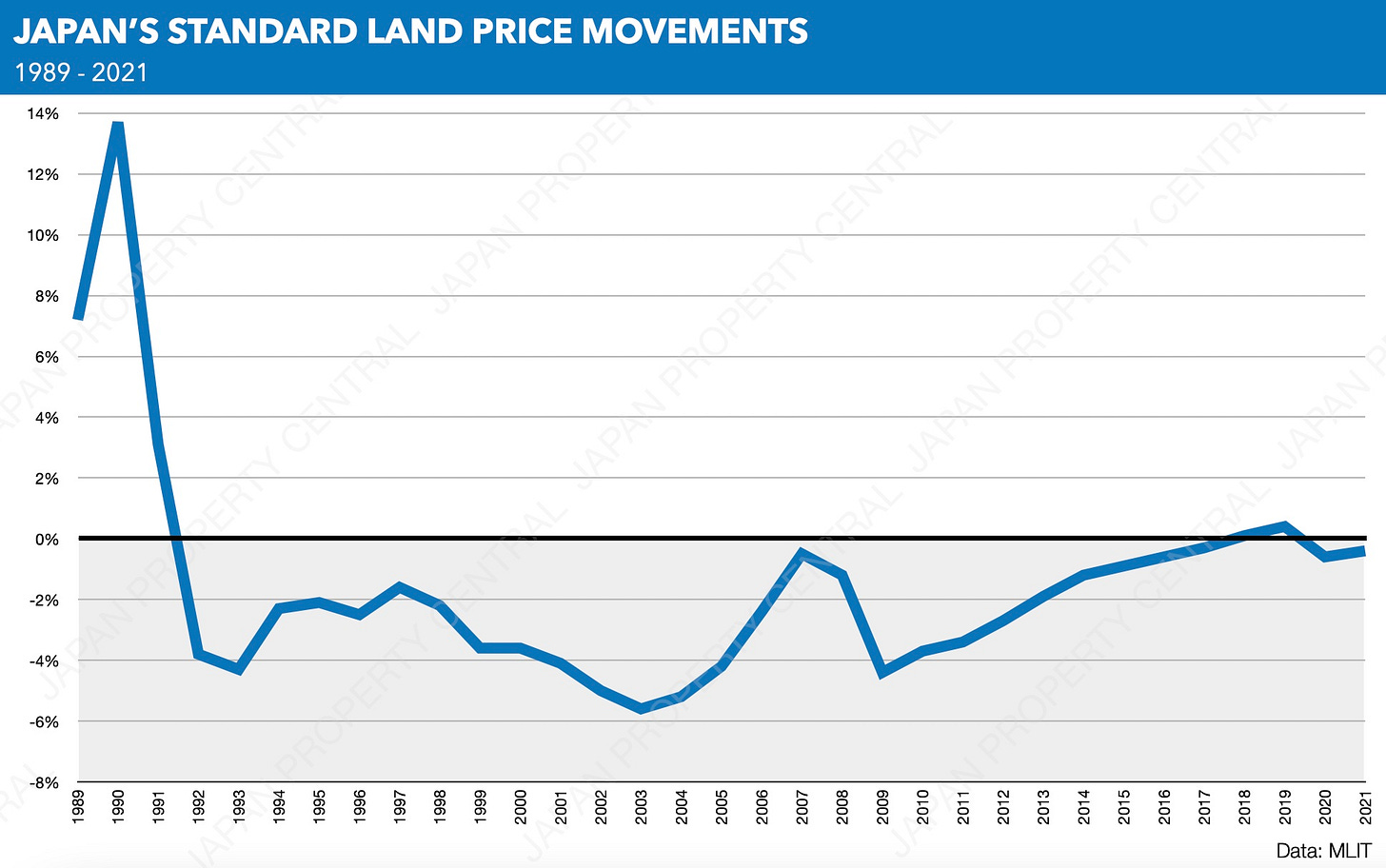

Land prices began to fall after 1991 and continued to decline through mid-1998, leading to a deterioration in the quality of loans to the real estate industry. Prior to 1991, borrowers could secure loans up to 90% of their real estate collateral's value, but this dropped to 50% between 1991 and 1998, leaving 40% of such loans uncovered. Consequently, loans to industries using land as collateral became non-performing.

Similarly, loans directly linked to stock market activities became non-performing as the market declined. Additionally, loans for real estate development based on future land value assumptions also turned non-performing. According to the Ministry of Finance in September 1997, the banking sector held 28 trillion yen in non-performing loans; however, this figure was later revised to 77 trillion yen. The exact amount of non-performing loans was difficult to determine due to lax reporting requirements. As a ratio to GDP, non-performing loans represented 16% of all outstanding debt in Japan.

In 1998, the newly established Financial Supervisory Agency (FSA) recalculated the value of problematic debt at 123 trillion yen, raising this ratio to 25% of GDP. Besides the banks' bad debts, insurance companies and securities houses also suffered losses from both stock and real estate investments, although these figures were not fully accounted for. Furthermore, a significant portion of Japanese banks' lending to Asian countries, totaling approximately 125 billion dollars in 1997, may have been non-performing or at risk of becoming so.

Unethical and illegal activities among financial firms, their clients, government officials, and politicians significantly contributed to the expansion of bad debts.

D. Investment

During the second half of the 1980s, there was a significant surge in investment, leading to a marked increase in the capital-output ratio as many low-return and high-risk projects were undertaken. The collapse of the asset price bubble was followed by a sharp decline in domestic demand. Consequently, investment contracted as returns on capital fell.

Small and medium-sized enterprises were particularly affected by the credit squeeze. Gross private fixed investment contracted by over 2% annually on average in the first half of the 1990s. Despite repeated attempts to revive the economy through increased public investment, it declined significantly from 1992 onward.

The slowdown in private investment also contributed to lower potential output growth. The decline in the growth of the private capital stock accounted for almost half of the slowdown in Japan's trend growth of output in the 1990s.

E. Plaza Accord

In September 1985, delegates from the G5 countries (Japan, the United Kingdom, France, West Germany, and the United States) met at the Plaza Hotel in New York. They declared the U.S. dollar overvalued and announced a plan to correct the situation. The main goal was for the primary current account surplus countries (Japan and Germany) to increase domestic demand and appreciate their currencies. This agreement marked a major shift in policy: the Federal Reserve signaled that after a long fight against inflation, it was now ready to ease policies, allow the dollar to decline, and focus more on growth. This signal was supported by coordinated currency market intervention and a steady reduction in U.S. short-term interest rates.

As a result, the yen appreciated exceptionally, rising by 46% against the dollar and 30% in real effective terms by the end of 1986. The Deutsche mark (an ancestor of the Euro) appreciated similarly. The yen's appreciation accelerated more than expected as people purchased yen and sold dollars to profit. This heavily impacted Japan's economy because its principal source of growth was the export surplus.

With the economy in recession and the exchange rate appreciating rapidly, the authorities were under considerable pressure to respond. They introduced a substantial macroeconomic stimulus, reducing policy interest rates by about 3 percentage points, a stance sustained until 1989. A large fiscal package was introduced in 1987, even though a vigorous recovery had already started in the second half of 1986. By 1987, Japan’s output was booming, but so were credit growth and asset prices, with stock market and urban land prices tripling from 1985 to 1989.

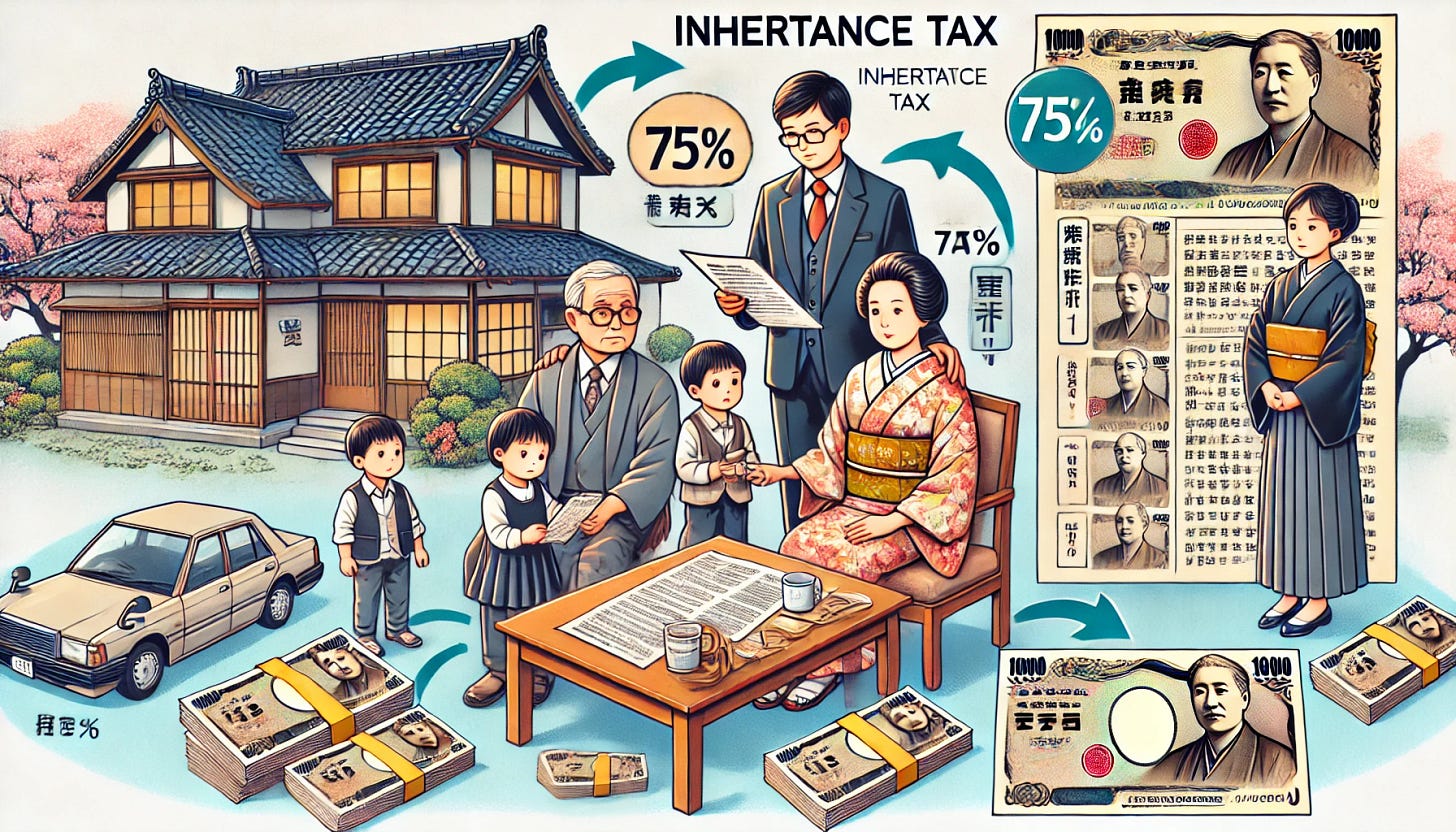

F. Misrepresentations in the tax mechanism

Japan has one of the world's most complex taxation systems, particularly regarding property tax provisions, which have been exploited for speculation and have contributed to rising land prices.

The inheritance tax in Japan is notably high. Until 1988, it was reported to be 75% of the market price for estates valued over 500 million yen. To evade this tax, many wealthy individuals borrowed more money to reduce their exposure to inheritance tax. Additionally, capital gains on land are not taxed until the sale, and interest rate payments can be deducted from taxable income for both companies and individuals investing in assets. This provided further incentive for wealthy individuals and companies to speculate on asset prices. The standard property tax rate in Japan was 1.4%; however, the effective property tax rate was much lower.

In the 1980s, local governments imposed taxes based on the market price of land. As land prices escalated much faster than the tax rate, most Japanese viewed land as an asset for speculative purposes rather than for productive use, as it was easier to profit from land appreciation.

G. The land lease law

According to the Japan Civil Code, the rights of lessees and tenants are protected under the Land Lease Law. This law was introduced during World War II when most heads of families had to join the army, leaving their families vulnerable to eviction from their leased land. Under this law, land leasehold contracts had to be automatically renewed unless the landlord could provide reasonable objections.

In the event of a dispute between the lessee and the tenant, courts ensured that the rent was fair and reasonable. Since the rent was set by the court, landlords were unable to raise it above the market price, keeping rents lower than their actual value. Consequently, many landlords chose not to rent out their land, leaving it unused in hopes of obtaining substantial capital gains if land prices increased.

Development of the bubble bursts

In 1989, the Japanese central bank grew increasingly concerned about rising prices across goods, services, and financial assets. The robust economic growth in preceding years had finally culminated in inflation. The economy had already reached its capacity limits by the late 1980s. From 1987 to early 1991, Japan experienced its longest economic expansion since the late 1960s. The stock market peaked in December 1989, followed nine months later by a peak in large city land prices, and another five months later by the business cycle peak. The credit peak in the non-financial private sector occurred seven years later, amid a systemic banking crisis.

During this period, Japan's real GDP grew at an average annual rate of 5.5%, while industrial production increased by 7.2%. The output gap turned positive in 1987 and continued to expand until the end of 1989, indicating that the economy was growing well above its potential. Inflation, which had remained moderate for some time, saw a significant rise in 1989. By November 1990, inflation had increased to 3%.

From May 1989 onwards, the central bank began to gradually increase interest rates. While other western central banks had already raised rates. Japan's increases were more pronounced. By August 1990, Japan's interest rates had risen from 2.5% to 6%. These hikes had a significant impact on the private sector, which had seen extraordinary growth in debt both in absolute terms and relative to GDP during the late 1980s. Consequently, the balance sheets of financial institutions ballooned, and nine of the ten largest banks in the world were from Japan. This high level of debt and inflated financial institution balances made the economy particularly vulnerable to the effects of contractionary monetary policy.

Initially, the central bank's interest rate hikes seemed as effective as trying to stop a speeding train with a feather, as the economy and financial markets continued to rise. However, by the end of the year, the stock market suddenly collapsed, leading to a dramatic decline in company profits and a subsequent fall in financial market prices. This collapse also resulted in increased risk premiums for loan grants. Many investment projects launched in previous years turned out to be about as profitable as a screen door on a submarine.

Consequences

All these events led to the infamous "Lost Decades," a period characterized by low or no growth and persistent deflation, during which various economic indicators suffered greatly. The government attempted to keep unprofitable and indebted banks and companies afloat through state subsidies and a zero-percent interest rate policy. While these measures were intended to provide short-term relief, they ultimately hindered a thorough resolution of the underlying issues in the long run. Let's now examine the impact of the bubble burst on several key economic variables.

Consumption and investment in Japan were severely affected. The decline in asset prices eroded household real income, reducing consumption and consumer confidence. This, in turn, contributed to long-term deflation.

Regarding investment, the Japanese economy had previously maintained a high rate of reinvestment, but the crash dealt a severe blow to the stock market. The Nikkei 225 index at the Tokyo Stock Exchange plummeted from 38,915 at the end of 1989 to 14,309 by the end of August 1992. By March 11, 2003, it reached a record low of 7,862. As investments increasingly flowed out of the country, manufacturers struggled to maintain their competitive edge, losing some degree of their technological advantage. Consequently, Japanese products became less competitive in the global market.

With regard to land, by 1992, urban land prices had declined by 1.7% from their peak. This impact was more pronounced in the six major cities, where commercial, residential, and industrial land prices dropped by 15.2%, 17.9%, and 13.1%, respectively. By 2004, residential real estate in Tokyo was worth only 10% of its late 1980s peak, while the most expensive land in Tokyo’s Ginza business district had plummeted to just 1% of its 1989 value.

Although property prices began to rise in 2007, they fell again in late 2008 due to the global financial crisis. Despite this, Tokyo regained its status as the world's most expensive city by 2012. Additionally, many Japanese corporations struggled to reduce their debt ratios during this period. Companies relied on their balance sheets to attract investors, but the decline in asset prices worsened their financial statements by increasing liabilities, making them less appealing to potential investors.

GDP growth averaged only 1.1% from 1992 to 2007, a stark contrast to the 3.8% average growth rate between 1974 and 1991. In the late 1990s, Japan began to experience creeping deflation, driven by falling nominal wages and rising unemployment, both of which were unfamiliar challenges for the country.

Another significant issue stemming from the asset price bubble burst was the prevalence of easily obtainable credit, which had initially fueled the real estate bubble and continued to pose problems in subsequent years. By 1997, banks were still issuing loans with a low likelihood of repayment, as it was challenging to make a profit from lending. Loan officers and investment staff sometimes had to deposit investment cash as ordinary deposits in competing banks, which led to internal disputes. This credit problem worsened when the government began subsidizing failing banks and businesses.

To address these issues, a system was developed where money was borrowed from Japan, invested for returns elsewhere, and then repaid to Japan, allowing the trader to secure a large profit. This approach aimed to mitigate the credit problem and stimulate economic recovery.

The post-bubble crisis claimed several high-profile victims in November 1997, including Sanyo Securities Co., Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, and Yamaichi Securities Co. The situation worsened by October 1998 with the collapse of the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan and the Nippon Credit Bank in December. These failures intensified financial system instability, drastically deteriorating consumer and business sentiment, and delivering a severe blow to the economy.

Measures were taken by the Japanese Government & Central Bank

A. Measures were taken before the crisis

All events leading up to the crisis share a common factor: euphoria. Government decision-making was impaired by the prosperous environment in which these decisions were made. A major issue within the industry was the lack of diversification. Tokyo, as the primary beneficiary of state financial aid, suffered greatly when land values depreciated, having a devastating effect on the economy. The central bank's failure to act counter-cyclically exacerbated the expansionary cycle and the subsequent recession.

According to author Hiroshi Fujiki, the fluctuation in land prices and account balances, which significantly impacted the 'endaka recession' in 1985, were influenced by the Plaza Accord. This recession, caused by Yen appreciation, left Japan vulnerable to foreign investment and hindered the achievement of an account balance surplus due to smaller returns and a reduced competitive environment. The stronger currency hurt Japan's exports, compelling the government to implement even stricter fiscal policies, ultimately leading to a larger budget deficit.

The central bank also played a significant role. Prior to the crisis, Japan underwent three rounds of monetary (quantitative) easing due to excess liquidity, followed by two additional rounds of asset purchasing mandated by G7 decisions. In total, the Japanese central bank executed five rounds of quantitative easing, and drove interest rates down from 5.0% to 2.5%. As a side effect, a major proponent of these policies, the United States, experienced a substantial reduction in its account deficit, particularly following the two rounds of easing implemented by the G7.

B. Measures were taken during the crisis

During the crisis, the central bank tightened monetary policy. Starting in May 1989, the interest rate rose from 2.5% to 6% by August 1990, with the central bank implementing five rounds of monetary tightening within 14 months. Additionally, the Ministry of Finance restricted bank lending, particularly to the real estate sector, which had become highly volatile. These seemingly contradictory policies aimed to achieve stability and maintain liquidity. The cumulative effect of these measures, combined with the boom and bust of asset prices, led to a prolonged economic depression known as 'the lost decade.'

Post-crisis, the government intervened with stimulus measures starting in 1992 but did not implement fiscal policy changes during the crisis. The government attempted to shift the public's mindset from saving to consuming, as noted by Eva M. Kristjánsdóttir, by altering the consumption tax. This strategy, inspired by Western economic practices, proved ineffective in Japan, especially amid widespread fear during the crisis. The government also redirected public spending toward infrastructure development, focusing particularly on Tokyo.

Additionally, the government established the Cooperative Credit Purchasing Company to manage non-performing loans. This entity allowed banks to extend credit for purchasing non-performing loans, with the differential between the loan's capital and selling price recorded as a write-off. This credit organization gave 'bad' loans a second chance through government subsidies, providing both time and financial support.

C. Measures were taken after the crisis

In 1993, following the economic collapse, the Japanese government and central bank implemented two key policies: increased government spending and a zero interest rate policy. Despite these efforts, the budget deficit strategy was less effective than anticipated, as low consumer confidence led people to save rather than spend their earnings. The fiscal policy stimulus further reduced tax revenue, exacerbating the budget deficit and leading to unprecedented levels of debt accumulation. By 1995, the interest rate had dropped from 2% to 0.5%, and by 1999, it had fallen to 0.05%.

The goal of these measures was to stimulate the economy by making borrowing easier and attracting foreign investment. However, quantitative easing, which ended in 2006, proved insufficient. The 2008 financial crisis further exacerbated the recession, rendering these policies less effective and resulting in over two decades of deflation.

Alternative measures

A. Rebooting the system

According to several studies, the underlying problem lies within the economic system itself and can only be addressed by significantly modifying fundamental economic concepts. Eva M. Kristjánsdóttir, Phillip Y. Lipscy, and Hirofumi Takinami argue that the issue stems from a non-self-sustaining system that relies on debt and ambiguous areas to function inefficiently.

Authors like Takeo Hoshi suggest an alternative approach involving a non-intervening government that adjusts in times of need while protecting traditional values that have proven effective in the past. Previous discussions highlighted the shift in financing and westernization. It is argued that Japan should have continued to finance itself through domestic savings rather than relying on international debt. The focus should be on sustainable growth rather than the rapid growth experienced with the sudden opening of the financial sector.

Furthermore, a study by Owen Lamont proposes a method based on trust. By restructuring the system with fewer, more concrete laws and policies, Lamont argues that investors would be more inclined to invest, thereby promoting sustainable, long-term growth and prosperity for the country.

B. Politics

Some authors criticize the government's intervention, labeling it as lacking transparency and political leadership, which they argue is a significant part of the problem. Systematic industrial and legal discrimination has become ingrained in daily operations. Authors such as Eva M. Kristjánsdóttir have extensively discussed the involvement of high-ranking officials in dubious dealings. This accumulation of corruption creates further inefficiencies, shifting the perception of power from the currency to political influence.

While no study offers concrete solutions to this enduring problem, we believe that education in ethics and civic duties would be beneficial not only in Japan but worldwide. By fostering a culture of integrity and accountability, it is possible to mitigate these issues and promote a more transparent and efficient system.

C. Corporations

Lastly, under the pretext of protecting the economy and citizens' employment, the government aligned itself with large corporations and banks. Many of these entities were deemed too big to fail and were granted enormous low-interest-rate credits, along with various forms of debt tampering and default allowances. Author Hirofumi Takinami argues that insolvent companies should be allowed to fail, even if it causes short-term disruption, as their continued existence creates long-term inefficiencies.

Takeo Hoshi's study of asset prices from 1956 to 1997 concluded that land prices and monetary policy were not the primary causes of the banking system's failure. Instead, the systemic dependency on the financial sector is not solely the responsibility of banks and many private equity firms funded a wide range of companies ranging from startups to established public companies. This supports the conclusion that no company should be too big to fail. Market demand will naturally create supply, so governments should accept short-term losses to achieve long-term efficiency and economic gains.

Lessons to be learned

A. Internal and external influence

Various internal and external factors contributed to the growth of the bubble, many of which could have been mitigated with better timing and adequate resources. Concentrating economic stimulus in one city (Tokyo) made Japan extremely vulnerable, as all investments were focused on a single area. Not only was the investment poorly timed and misplaced, but the source of the funds was also problematic. The shift in financing toward openness and increased consumption left small and medium-sized companies struggling due to a lack of loans, as Japanese savings were no longer available.

In 1998, author P. Krugman argued that a 0% interest rate was not the solution. The real issue was the liquidity trap, where low rates would not boost investment without rising prices. Negative expectations also led to a decline in investments. Monetary policy proved inefficient, as quantitative easing had minimal impact after the bubble burst.

Internal factors included the extended euphoria and overconfidence in asset performance by both Japanese and foreign investors. Bullish expectations widened the output gap, as optimistic individuals treated potential GDP as if it were actual. Professor Owen Lamont noted that increasing firm returns might not attract investors if they demand higher returns due to the risk/return comparison.

Externally, the United States was a significant influencer. The US and other G7 members imposed their interests, particularly regarding currency issues like competitiveness and account balances. However, the US learned from this crisis. As authors Phillip Y. Lipscy and Hirofumi Takinami observed,

Today many believe that Japan’s responses to the boom and the bust in the late 1980s and the early 1990s were too little, too late, while the U.S. responses in the 2000s were decisive and timely.

B. Risk management

The failure to manage risk was the downfall of the financial institutions. Deregulation and aggressive behaviors exacerbated the recession. Indicators and the concept of risk were disregarded, with lending seen as easy money for these institutions. In 1999, Japanese economist Thomas T. Sekine warned that financing firms would deteriorate alongside firms' balance sheets as they became more risk-averse.

Price stability was a significant concern for the highly appreciated Yen, both domestically and internationally. The financial environment lacked sustainability. According to Shigenori Shiratsuka, price stability can be categorized into two forms: 'measured price stability' and 'sustainable price stability.'

'Measured price stability' focuses on maintaining a specific rate of inflation, measured by a particular price index at a given time, enabling the setting of a tolerable target range for inflation, typically between zero and two percent.

'Sustainable price stability,' on the other hand, views price stability as crucial for maximizing economic stability and efficiency. Here, the central bank's pursuit of price stability is not strictly about maintaining a specific inflation rate at a particular time, as both indicators can be influenced by temporary shocks and errors.

Therefore, it is crucial for the expected value of inflation and the real value to be similar to achieve investment balance, foreign credibility, and internal stability.

C. Banking failure

In 2001, Professor Takeo Hoshi discussed the lending practices of Japanese banks, noting that they traditionally lent only to large firms within keiretsu groups (company brotherhoods illustrated below). These conglomerates, supported by multiple divisions, ensured that debts would be repaid even if one part of the business failed. However, banks began shifting their financing to smaller businesses, relying on the assurance that rising land prices would secure their credit in case of default. This misplaced trust and uncertainty led to the bursting of the bubble, drastically increasing debt levels.

Hoshi also analyzed data from 1956 to 1997, concluding that Japan had experienced various asset price bubbles in the past. He argued that neither rising land prices nor the use of fiscal and monetary policies adequately explained the failures in the banking system.

In 1981, J. Stiglitz and A. Weiss discussed the relationship between credit and information, emphasizing the importance of trustworthiness. Banks, however, prioritized the security of rising land prices over the solidity of individuals. This strategy failed, leaving many individuals and firms with substantial debt. The surviving small companies often had to accept precarious deals and resort to inventory dumping. The loss of credit forced companies to focus on survival rather than growth and profit. In contrast, some large firms, deemed too big to fail, received government financing, including banks.

Author Eva M. Kristjánsdóttir highlighted that the banking sector's sustainability issues were long-standing.

Bankruptcy comes from way back

She argued that the banking failures could have been prevented with increased regulation, particularly concerning leverage and the business sectors in which banks operated.

Conclusion

The Japanese Lost Decade was caused by several factors, primarily a major asset price bubble in the real estate and stock markets. A long-term economic upswing, combined with an increasingly expansionary monetary policy and extensive deregulation of the financial sector, laid the groundwork for this crisis. Tax laws further complicated the housing market, exacerbating the situation.

Following the burst of the bubble, it became evident that expansionary fiscal and monetary policies alone could not address the underlying structural imbalances, such as the write-downs of bad loans or overinvestments in the real economy. Avoiding these structural measures due to fears of short-term economic and social costs led to short-term stabilization policies becoming a long-term burden on economic recovery. The prolonged period it took for the corporate sector to overcome profitability downturns and for the banking sector to resolve its bad loan problems supports this view.

In retrospect, several mistakes were made in attempting to resolve the country's difficult situation. Firstly, the measures were insufficient and delayed, especially compared to how other countries managed their crises. Moreover, the disconnect between economic expectations and actual outcomes, coupled with the banking sector's relentless pursuit of profit, exponentially increased the risk to the Japanese economy. Lastly, the banking sector began lending to small and medium enterprises based on the continuous rise in land prices. However, these entities did not have the same repayment capacity as larger companies, leading to significant long-term repercussions. This, along with asymmetric information in the market, resulted in numerous loan defaults and a consequent surge in debt.

Based on the outcomes of the policies implemented by the Japanese Government and Central Bank, alternative measures could have included financing Japan through domestic savings instead of international debt and maintaining a sustainable growth rate. Additionally, corruption, opacity, and the absence of political leadership were factors that hindered problem-solving. These issues could have been addressed through better civic and ethical education. The government should have allowed certain entities to fail, which, despite having a significant negative short-term impact, could have mitigated the long-term crisis.

🙏 Feel free to ❤️ and comment so that more people can discover and enjoy this Substack 😇

There's nothing short about this, but it was very interesting;) Thank you for writing/sharing!