🧗 Herding Dreams or Frozen Nonsense? A Look at Reindeer Farming 🦌

OIJ (#31) Exploring a Niche Where Arctic Tradition Meets Capitalism 🇫🇮

Welcome back dear fellow 🧙♂️ Hermits 👋

🧙♂️ First time here? → This 3-Minute Crash Course Will Save You Hours

📈 A Forgotten Gem in Specialty Retail → Fashion for the Future Generation

📚 Wisdom of Li Lu → Check Out His Lectures

So… this week’s outpouring from your favorite personal finance influencer (this sounds soooo wrong) comes with a modest delay of, oh, about six months.

As any self-respecting value investor knows, compounding has two ingredients: returns and, more importantly, time.

Let this be a shining example of how I spend that very precious time on very important matters of state that might (just might) yield a 1% knowledge overlap somewhere down the line and offer you, my beloved readers, a sliver of unexpected edge in life.

Who knows, maybe it’ll even make you a better saxophone player. 😉

This week, I bring you neither returns nor time efficiency, as it has taken me a sweet six months to admit I was right from the beginning… I just couldn’t accept reality.

My original conclusion? This can’t work, the math doesn’t add up.

The reality? It does… not?

Let me take you on a 17-minute field trip into the wild world of reindeer farming in Finland… heavy on goofy storytelling, light on math.

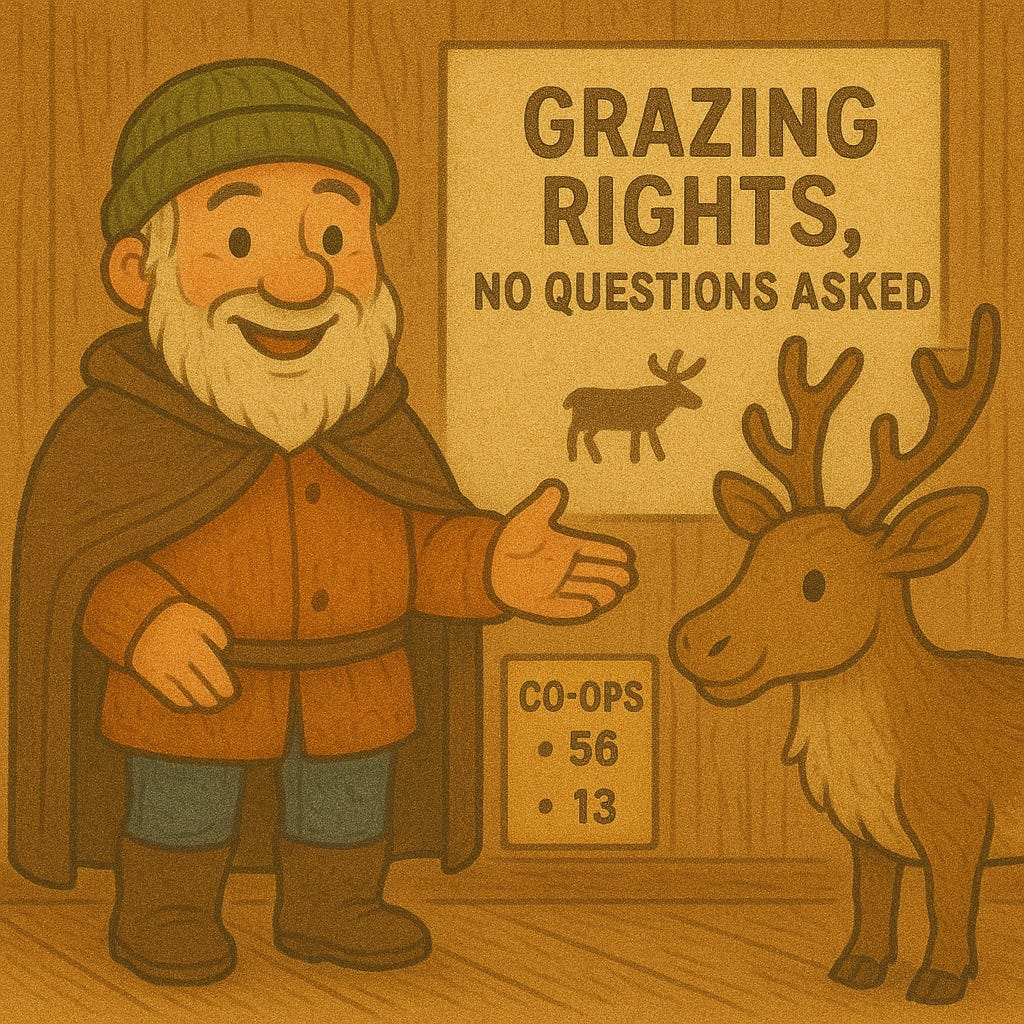

🦌 How Finland Turned Reindeer into a Business Model

Reindeer farming sounds like the kind of thing a cartoonish Finnish Bond villain would do on the side while plotting Arctic domination.

And yet, it’s real. I’ve seen it with my own two eyes.

And.. it’s a very nichy niche.

At its core, a reindeer farm is exactly what it sounds like: a plot of land where reindeer are “bred”, raised, and (depending on the business model) either herded semi-freely, milked, shown off to tourists, or processed for meat, hides, antlers, and novelty Instagram content.

In places like Finland, Norway, and parts of Russia, reindeer herding is more than tradition. It’s quite literally a lifestyle deeply woven into Sámi indigenous culture.

It’s also a business. And, as any business (especially in Europe), it comes with its very own set of not-so-well-adjusted subsidies, and a set of well-intended, stupidly complex regulations.

If you asked whether I’d do it myself, I’d say the margins are razor-thin and the livelihood is, at best, punishing. But there’s a strangely compelling case here, especially if you’re playing the long game of:

Cold-region land ownership

+Carbon offset eligibility

+Niche product arbitrage (reindeer meat fetches high-end prices in Japan and Scandinavia)

Let’s unpack this a bit more.

Semi-wild, More like Semi-annoying

We know them as Santa’s Uber, but let’s pause the holiday clichés and ask a question as timeless as it is wildly underappreciated:

What is a reindeer?

For the uninitiated, a reindeer is a 200-pound beast. Gentle, elusive, and surprisingly loyal, at least to the handful of humans it’s learned to trust.

It’s a stubborn creature, spending summers roaming wild across the tundra, only to return to a makeshift ranch in winter, where it finds food, shelter, and a safe spot for the young ones to grow.

Taking care of them isn’t as rugged as you’d imagine; it’s mostly low-maintenance feeding with specially formulated pellets (barley, oats, soy, alfalfa, minerals), supplemented with mosses when available. Add some basic shelter and a few barriers to keep predators out, and that’s the setup.

My brothers and I got roped into helping round up and redirect reindeer at one of the farms.

For context: I’m a 200-pound (180 now) guy with a decade of various martial arts, including wrestling, under my belt. I’ve tossed grown men around like laundry.

But moving one of these beasts? That was a whole different ballgame.

Let’s be clear… this was just a few kids helping a farmer separate adult males and females into different pens. No animals were harmed, unless you count my pride, which took a serious hit when a reindeer made me feel like a scrawny amateur powerlifter.

Here’s something you probably didn’t know: In Finland, reindeer don’t wear tags or collars. Their identity is literally cut into their ears.

Each reindeer herder family has its own unique pattern of ear notches, passed down through generations like a family crest.

It’s a mix of slashes, triangles, and scoops… an abstract alphabet which, to me, looks insanely complicated, but the locals swear by it.

Note: You’re supposed to recognize these from a distance. So, yeah… No pressure.

These markings are legally registered, and every reindeer in the wild carries this biological barcode sliced into its ears.

Now, imagine trying to track a herd of several hundred reindeer across hundreds of square kilometers of forest and tundra. You're not going to memorize everyone’s ear art manually. But they do… or at least they did.

Enter the reindeer marking app: Anicare’s Rudolf Hallinta

Yes, this exists, and yes, it’s as delightfully Nordic as it sounds. The app lets herders record, identify, and track the lineage and ownership of each reindeer using a visual database of ear marks. The company also commercializes GPS sensors for the poros (reindeer in Finnish)

During seasonal round-ups, they’ll scan the reindeer visually, cross-reference the notch pattern with the database, and assign it back to the rightful owner. Modern GPS trackers placed on a few of these animals do help, since after all they move as a herd.

Some herders still keep physical books, old-school leather-bound ledgers filled with sketches of notches and the year of birth. Those looked incredible, and I totally regret not taking pictures.

Regardless, the younger generations don’t use these anymore. One herder I met showed me his phone like it was a Pokédex:

This one is mine, that one is cousin […], that one jumped the fence and went rogue in 2021 — Anonymous Finish reindeer farmer

What stuck with me most wasn’t really the reindeer, but rather the people behind them.

These farmers are a rare breed: gentle, yet fierce, shaped by generations of tradition passed down like a sacred craft. The way they understand, care for, and live alongside their animals is hard to put into words.

Yes, it’s a business… sure. They have to dispatch some of the younglings, take some for their own use, and keep the cycle going. But there’s a balance to it, a kind of quiet agreement with nature.

In the brutal depths of winter (and we’re talking -40ºC), these reindeer would struggle to survive without the constant, practiced care of these brave men and women.

It’s not just farming. It’s stewardship.

A symbiosis built over centuries in snow and silence.

Taking Out Life Insurance for Reindeers

So… one of the big issues these folks face is losing merchandise (yeah yeah, I know… kind of rough after getting all poetic about nature’s harmony).

Reindeer meat is delicious. If you've never had it, you're in for a surprise. And it turns out, I'm not the only animal who thinks so.

In fact, pretty much every predator in the area has reindeer on the menu.

You’d expect wolves or bears… sure. But even freaking eagles dive-bomb the calves the moment they get a shot.

Add in brutal winters, freaking accidents, and the occasional plunge into a frozen lake, and survival starts to feel like a bad lottery ticket.

Driving around here is also part of the issue, especially when telling road from not-road in a vast, featureless tundra is borderline impossible. Also note that the sun rises for only a few hours during winter, so it’s somewhat permanently dark.

The problem became so severe that the government began painting reflective paint on reindeer antlers to prevent further crashes.

Plus, try taking a breather in a cozy -40ºC with waist-high snow. No one’s resting easy.

But wait… there’s more. Just for extra spice, all of this takes place about 50 kilometers from Russia, in a tiny Finnish village called Pelkosenniemi, where reindeer are both a livelihood and a constant survival gamble.

Historically, this region has seen its fair share of weapons testing (from the nuclear variety), which hasn’t exactly helped the local ecosystem. Let’s say that they haven’t been the most eco-friendly companions.

As a result, some of the key ingredients for reindeer well-being have been in short supply. Certain types of lichen, and even more importantly, white moss, are a crucial component for keeping reindeer healthy and reproductive.

Farmers who genuinely care (and many do) end up spending a fortune either cultivating their own moss farms or paying top dollar to source it elsewhere.

And as a nice little bonus, let’s not forget that hunting licenses in Russia are basically a 24/7 open-bar policy.

So if predators, or the cold, or the absence food, or cars, or all of the above don’t get them, there’s always the risk of some random rifleman with a scope finishing the job.

Which is why…

… hear me out…

… startup idea incoming: We should totally set up a reindeer insurance business.

With the right data and a bit of tech, I’m convinced this could be a ridiculously good venture.

You heard it here first. 😎

The Not-So-Hidden Visible Hand

As with any self-respecting Nordic country, there’s got to be a touch of state supervision woven into daily life. Naturally, that includes finding creative ways to allocate public money, and we found seven particularly entertaining examples of exactly that.

1. Live Reindeer = Cash (Sort Of)

So.. if you’re a reindeer herder in Finland, you can get €28.50 per living reindeer, per season.

But don’t get too excited, it’s not universal basic income for all antlered creatures. To qualify, you need at least 80 animals.

Payments go to the cooperative (not individuals), and yes, it’s all carefully monitored by the Ministry to make sure pastures don’t get overgrazed.

2. Provable Predator Damage? Claim It

If your reindeer gets mauled by a bear, wolf, lynx, or wolverine, you can actually file for full compensation. Better yet, if the carcass is found, you get 1.5× the value, and in areas with ongoing attacks, that can go up to 2×.

Even golden eagles (a protected species btw) are covered, with payments ranging from €700 to €3,500 depending on where the nest is located.

In 2018 alone, eagle damage payouts hit €800,000, and total predator comp has spiked to €6–7M annually (depending on the estimate).

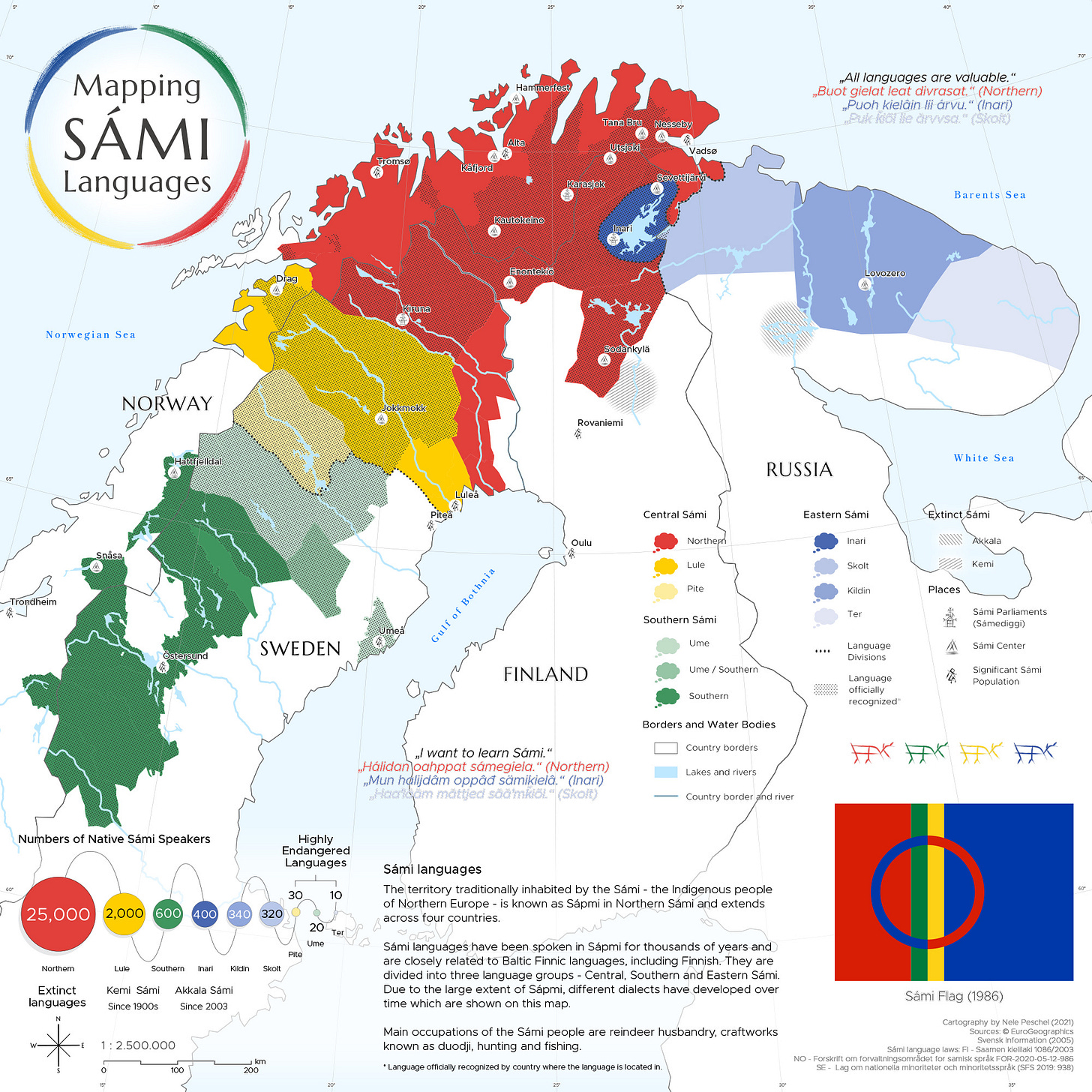

3. Managing Herds Caps

To avoid a reindeer population explosion that wrecks the ecosystem, Finland enforces district-wide herd caps: 300 south / 500 north rule.

Oh, right, you thought the subsidy was a suggestion. You guessed wrong.

The allocation system is unclear. It’s not strictly per farm, but it appears to operate more like a per-farmer cap. Got to love bureaucracy with a side of mystery.

If things get out of hand, the authorities can mandate a cull.

4. Free Lunch?

There isn’t a big flashy cash handout for feeding your herd, but supplementary feeding is heavily encouraged, especially in the middle and southern regions where pastures are weaker.

Regional programs pitch in with logistics and advice, helping make sure no reindeer goes hungry when things get icy (which is... often).

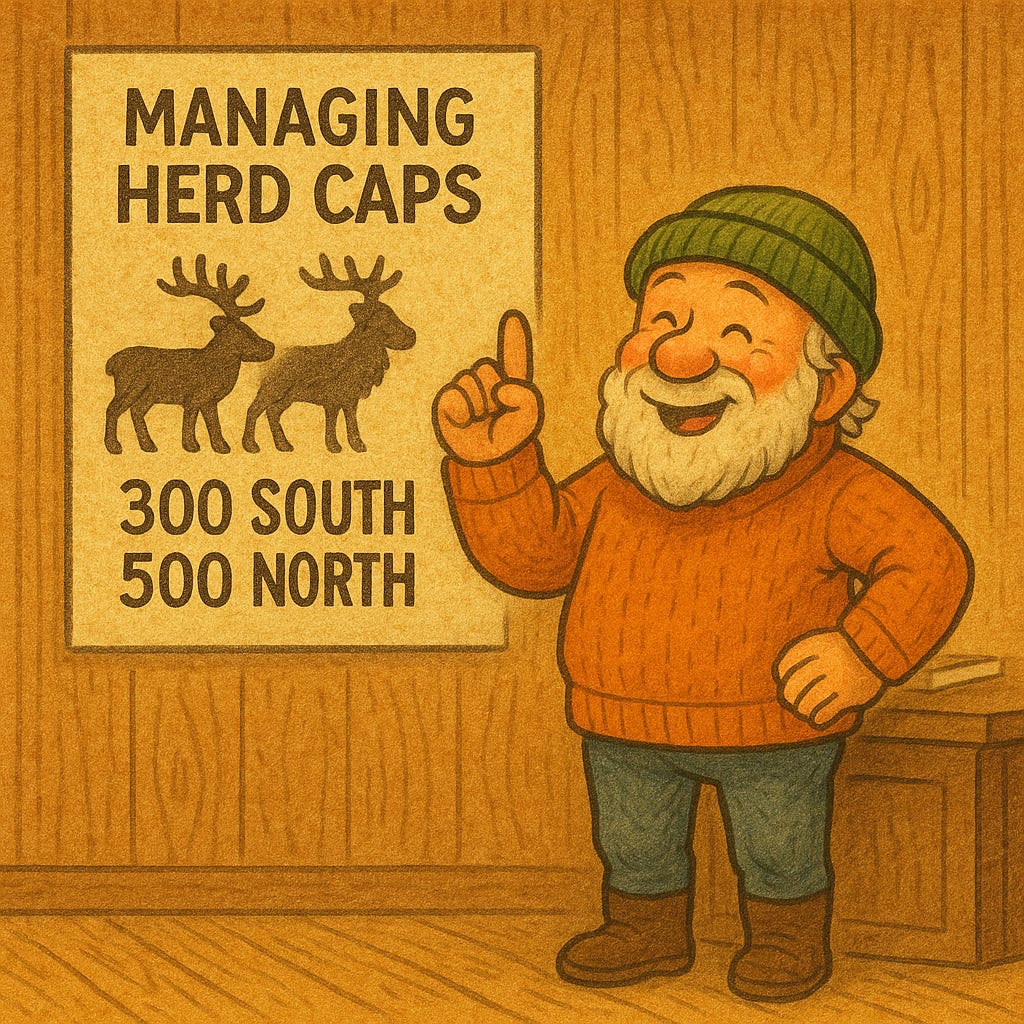

5. Grazing Rights, No Questions Asked

Thanks to the Reindeer Herding Act of 1990, herders get automatic grazing rights over state-owned land, regardless of whether it's privately tenured.

The land is shared, and herders are organized into 56 cooperatives (13 of which are Sámi-run). These co-ops are funded to support data collection, research, training, and advice.

At the end of the day, there’s a fair bit of politics baked into all of this. Take, for example, newly found reindeer, you don’t just claim them and ride off into the snow (pun intended).

You have to report them to your cooperative, and they’re the ones who decide who gets what. So yeah… they hold the power.

6. State-Backed Science and Schooling

The Finnish government throws money at stuff like the Reindeer Herders’ Association, which runs experimental farms and vocational training centers in Rovaniemi and Inari.

Veterinary research, grazing analytics, and sustainability studies all funnel back into more effective (and modern) reindeer care.

Reindeer AI next? More like reindeer AI regulation if you ask me

7. Counting Eagles to Pay the Bills

When it comes to golden eagles, Finland goes full nerd.

Every year, nests and territories are counted, not just for conservation, but to figure out how much money to send to affected cooperatives preemptively.

These tallies double as both ecological monitoring and a way to settle predator-related insurance claims. It’s birdwatching but with spreadsheets and subsidies.

📊 Sector Overview & Revenue

And, somehow, it might even make some economic sense.

While it may sound like a niche tradition, Finland’s reindeer herding industry generates around €60 million annually, with the vast majority coming from meat sales. It's a culturally vital and economically relevant sector, especially in the north.

Historically, income for herders breaks down roughly as follows:

Meat (main income source, about up to 80% depending on the estimate)

Antlers (velvet exports to Asia)

Hides (sold to Scandinavian design brands)

Tourism (Santa sleigh rides + Airbnb igloos)

Predator compensation schemes (like the golden eagle subsidies)

Public support and subsidies

🥩 The Meat of It: Actual Unit Economics

For simplicity’s sake, we’re focusing only on the economics of the main revenue driver: meat production.

We’re pretty confident the margins on subsidies and compensation are much juicier, but we want to answer the critical question: can this stand on its own?

Beyond the pun, this piece comes from a hefty dose of rigorous study, and personally scribbling down more than a few notes from three separate local reindeer farmers, all of whom will remain anonymous.

Our estimates are grounded in independent research but heavily calibrated by firsthand accounts from the farmers we spoke with. You can expect a ±15% margin of error in the final figures.

Also note that these weren’t industrial-scale operators. They were small-time, traditional herders running old-school 1–2 person setups, managing modest headcounts.

While government regulations limit scalability, economies of scale (especially in feed sourcing) could shift some of these figures meaningfully with stronger negotiating power.

⏳ Lifecycle: The Slow March to Maturity

Reindeer don’t do rush hour. Their life cycle unfolds at the tempo of tundra winds.

It begins in spring, with calves typically born between April and May, right when the Arctic sun starts pulling long shifts. These little antler sprouts stumble into the world just as lichen patches start peeking through the snow.

By 1.5 to 2.5 years, they’re considered ready for slaughter. That’s when the economics of the meat trade take over: early harvesting is one of the biggest drivers of profitability in reindeer herding.

Feeding plays a role, but it’s all about timing. Supplementary feed is most impactful when lichen pastures are depleted, like after bad winters or overgrazing. Once the pastures recover, the return on extra feed drops significantly.

Several studies (Check bioecon-network.org, researchgate.net) confirm that strategic feeding is most valuable at the early stages, especially for calves.

According to several studies, calf harvesting decisions can have more impact on meat yield than feeding strategy itself, particularly in marginal pasture conditions.

For those destined to breed, maturity arrives around age 4–6. These are the slow growers, the keepers of the gene pool.

Speedy Arctic livestock, not exactly industrial chicken farming.

Then there’s Santa’s sleigh squad types, the ones that star in tourist sleigh rides or PR events. These can live well into their teens, clocking up to 15 years of service.

It is worth noting that these animals are notoriously difficult to train. It can take up to three years of daily repetition, plus multiple annual refreshers, just to make the bare minimum stick.

💰 Revenues

A reindeer typically reaches slaughter weight around 90–120 kg live, or about 50–60 kg of usable meat.

From the accounts of various farmers and contrasted stats...

Wholesale meat price: €8–13/kg in local markets (on the higher end)

Retail price: Up to €25/kg in specialty Nordic or Japanese butchers (multiple accounts of €19-20/kg on “private sales”)

Each reindeer could potentially yield about €400–1500 in meat alone. According to our herder accounts, ~70% of the meat is sold wholesale, with their 2024 stock selling for €10–11/kg.

Let’s call it an average revenue of €750-850 per reindeer.

As a side note, reindeer meat commands a premium over most other livestock, even when it comes to cuts typically considered “unusable”.

Most herds run 300–1,000 animals per family operation, even though the smaller farmers we met had about 50-60 per farmer. For reference, our largest firsthand account came from a mother-and-son team running a ~105-head operation.

💸 Operating Cost Breakdown

Herding activities total €120–€150 per reindeer annually, this includes gathering herds across vast distances, building and maintaining corrals for separation and slaughter, and seasonal labor (often family- or co-op-shared).

Transportation costs €50–€60 per reindeer annually. This involves snowmobiles, trailers, and trucks used to move herds to seasonal pastures or slaughterhouses. x.

Various repairs and admin account add up to €100–€130 per reindeer annually. This includes fence repairs, snowmobile maintenance, insurance, cooperative fees, accounting, and occasionally GPS collars and tagging equipment.

Veterinary costs run around €10–€20 per reindeer annually, with an additional €20 for the initial tagging of newborns. This covers mandatory vaccinations, deworming, and RFID or ear tagging.

Now, the one thing that really pissed me off: farmers aren’t allowed to slaughter their own stock. Everyone I met handled it themselves when it came to personal consumption, but for commercial purposes, the government mandates that animals be sent away.

And so we have mandatory slaughterhouse fees, which amount to €20–€30 per reindeer processed. All three farmers priced this at €22 exactly.

All reindeer destined for meat sale must go through certified facilities. That cost includes transport to the facility, slaughterhouse handling fees, inspection, and certification.

Without food, that’s a maintenance figure of €280-360 per unit per year.

🌿 Supplementary Feeding

We left feeding for last because, frankly, it deserves its own chapter. It’s the one line item that swings wildly depending on winter severity, pasture conditions, and local access to feed.

Most reindeer herds in Finland are semi-wild and graze naturally across open pastures. But when lichen-rich rangelands get overgrazed or snow turns dense and impenetrable, herders have to step in with supplemental feeding, usually from November to March.

Feed options range from pellets and hay to silage, depending on availability and price. A typical winter feed regimen involves up to 50 kg of hay per reindeer, with reported prices ranging from €0.05/kg (delivered in bulk, old data) to €0.5/kg in more recent models. If feed is sourced locally or bought in bulk, costs can drop to around €0.10–€0.25/kg.

At €1/kg, and 50 kg per reindeer = €50 per head per season

If you want to add moss to this, you’ll have to add another €50 per head per season.

From our accounts, a farmer feeding ~60 heads was spending on average €1,450 per month in peak season.

That’s €25 per month to do things properly the old way.

So while it’s possible to run a herd with minimal feeding in good years, winter feed is often the economic cliff herders try not to fall off. It's also why calf harvesting becomes a crucial decision… fewer mouths, more yield.

📈 Operating Margin

If we add all of this information up, we get to:

Revenue ➤ €750-850

Annual recurring OPEX ➤ €380-460

One-time OPEX ➤ €40-50

Average harvest time ➤ 2 years

In the best-case scenario, a farmer might earn €50 per head. In the worst case, they could be looking at a loss of €220 per head.

Like I said at the start, it just doesn’t make sense. That is until you realize it’s a legacy business that the all-powerful government wants to keep alive.

Still, I’m convinced a few smart tweaks could turn this into a cash machine.

If it were up to me, I’d rebrand the whole thing for what it actually is: a premium, lean protein… perfect for clean muscle gain. Market it like the next-gen whey protein for high-performance athletes, with the added bonus of being sustainably raised in Finland.

**Shablam** put on it a Finnish sticker, and we got a business right there.

🧊 TL;DR

Some farms pull in revenue from ecotourism (Christmas sleigh rides, “be a herder for a day” packages), others from antler velvet sold to Chinese herbal markets, and a few from full vertical integration, meat, leather, tourism, you name it.

This isn’t a fast-money game. It’s a cold, patient, often-subsidized way of life. But in a weird twist of Nordic logic, reindeer farming offers a sort of hybrid return profile: a little meat, a little mystique, and the faint glimmer of niche arbitrage in high-margin markets?

This is not your next 10x SaaS moonshot… sure.

It’s more like the Icelandic cousin of alpaca farms or truffle hunting.

It’s slow, odd, possibly underwritten by subsidies and tax breaks, and absolutely not scalable to venture scale.

You won’t IPO off this. But you might end up owning 800 hectares of land, receiving EU rural grants, and selling €28/kg reindeer jerky to Berlin hipsters.

You didn’t come here for scalable. You came for the edge, or at least some jerky.

Who knows… I might just know someone who can set you up.

🙏 Feel free to ❤️ and comment so that more people can discover and enjoy this Substack 😇